“The European project has suffered and suffers from a structural blame game from the member states.” —Ana Palacio

“You need to have a common platform within the European Union… otherwise, things will definitely go apart.” —Magnus Schöldtz

The pandemic has exposed the fragility of governmental institutions around the world, and the European Union is no exception. “I would say that the worst was when we saw the internal market, the four freedoms”—the movement of people, goods, capital, and services—“disappear,” says former Spanish Foreign Minister Ana Palacio, who also served in the European Parliament and is an expert on European legal issues. “From one day to the next, borders were closed. It was each man for himself: If I had a mask, I wouldn’t share it.”

In a recent New Thinking for a New World podcast, Magnus Schöldtz, a longtime Swedish diplomat and adviser to the Wallenberg Foundations, agreed that it was unnerving how quickly the collective structure of Europe seemed to disintegrate. “Sadly enough, some very national and protectionistic instincts kicked in,” Schöldtz says. “The panic surrounding the storage or availability of critical equipment and safety equipment … All sense went out of the room with regards to the principles of the single market and the supply chains.”

But Schöldtz and Palacio are optimistic—or at least hopeful—that the worst is past. “Europe has this strange tradition of developing through crises, and this is a crisis that we cannot waste,” observes Schöldtz. Palacio puts it more aggressively, arguing that the early stumbles and outright bad policy choices will not be repeated. Next time, she says, “we will react in a more intelligent way. Yes, this for sure, because we will learn. In Europe, we learn from our mistakes.”

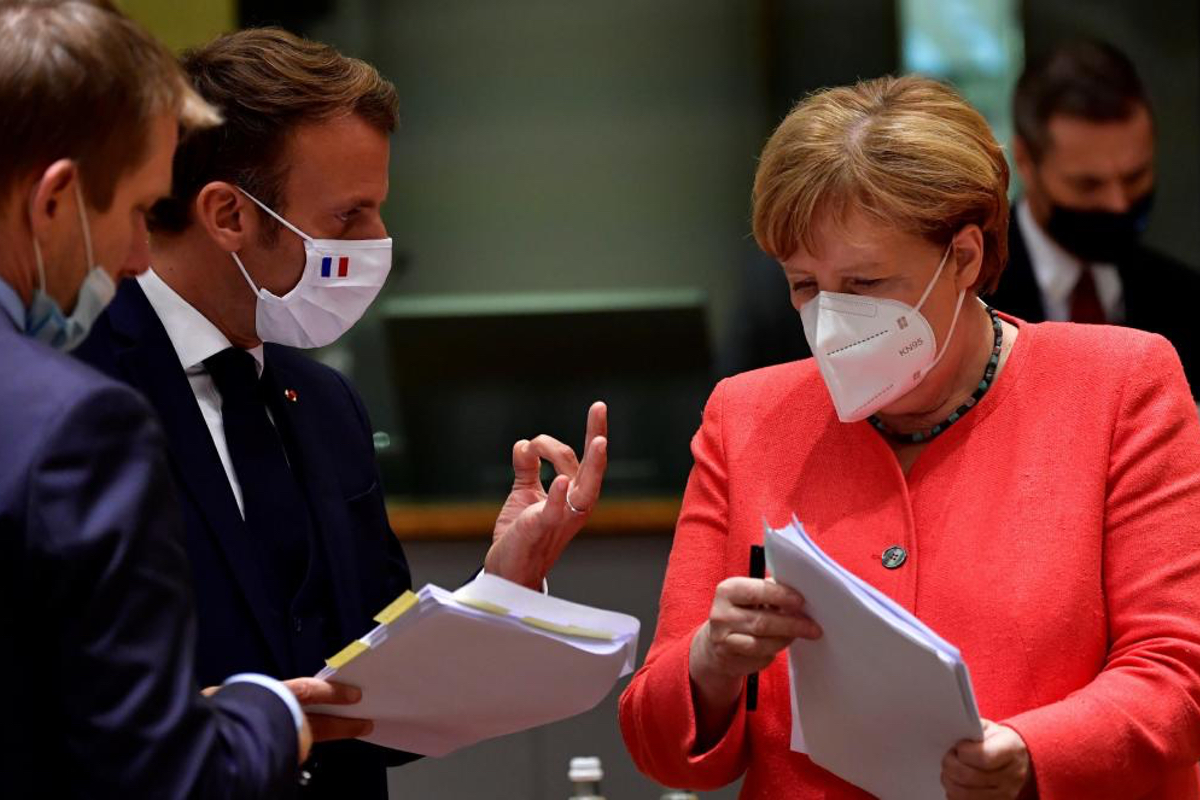

Exhibit A of that learning process was the fraught European summit in July. After four days of hard bargaining, the 27 heads of government agreed to a massive economic support package, to be disbursed partly as loans and partly as grants, and to be funded by a combination of borrowing and taxation at the European level—none of which had ever happened before. Schöldtz proudly points to that outcome: “At the end of the day, there was an agreement, there was a common will”—one that bridged dramatically different interests and demands among the member states.

Palacio believes that this historic agreement was possible because national leaders inEurope recognized the need to combine “interest with responsibility.” She argues that her own country, as well as Portugal and Greece, have shown the necessary responsibility when they implemented deep and painful structural reforms over the past several years, following the financial crisis. Schöldtz agreed that it was in the interest of economically conservative countries like Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Austria “to make sure that the markets in southern Europe … continue to function so that we did not see a crunch in demand that would then hit our industries.” Palacio sums it up, saying, “This interest and this responsibility is what adds up to solidarity, because we are in it together.”

Historic agreements notwithstanding, Europe is not yet out of the woods. Schöldtz highlights the need for competitiveness. “We need to look into how we invest in our future in terms of R&D, sustainability, and digitalization,” he says. “We are lagging behind both China and the U.S. when it comes to digitalization, for instance.” If Europe does not become more competitive, “we can forget the rest.” In that case, “We will be a soft power for the foreseeable future.”

Palacio concurs: “The fourth technological revolution—if we miss this one, we will consolidate a trend that unfortunately is there … Europe today is more the chessboard than the chess player. … Yes, we have to get more competitiveness, but we have to get our ideas together as well. “

By way of example, she points out that the E.U. lacks a common approach to China. Countries like Portugal and Greece want few restrictions on Chinese investment into Europe, while France and even Germany are increasingly inclined to block the Chinese from acquiring companies in their countries. “We cannot have 27 positions vis-à-vis China,” she declares. “It’s very difficult to speak about Europe in the world or the European Union in the world with such differences.”

In that spirit, Henry Kissinger famously (and factiously) once asked, “Who do I call if I want to talk to Europe?” In a year when Europeans struggled to find a common response to Covid-19, never mind China, that question seems still to be relevant. “Frankly, the problem here is that we have an ambivalent—not reluctant—an ambivalent leader, and this is Germany,” Palacio says. “When Germany leads, Germany gets things done. … Then there are areas where Germany doesn’t want to lead, either is absent or doesn’t participate—for instance, defense—and where things do not happen.”

For Schöldtz, the weight of history and the upcoming retirement of Chancellor Angela Merkel add up to a German preference to “lead from behind”—and he hopes that the “French President will be there to fill the void.” He also believes that countries like Sweden and Spain are critical to ”making sure there is sufficient transparency in that Franco-German cooperation.”

But, is that enough in the face of challenges like Brexit and a Trump-led United States?

Brexit is fundamentally affecting how Europe works. “For the first time, we see that the project is not irreversible,” Palacio asserts. “Now we have to come to terms with reality.”

Among other things, that means contending with the lost heft of Britain’s economic, military, and intelligence, as well as with the loss of its mediating influence in E.U. negotiating rooms. Schöldtz says nations like Sweden have lost a likeminded backer of its preferred policies, while Palacio believes Europe will miss the U.K.’s practicality. “Magnus, you will miss them, because they were the ones that would take the frontline in just putting on the table positions that you would defend from the trenches,” she says. “Even for a country like Spain, the voice of the U.K. will be missed, and it will be missed among many other areas because of their Atlanticist vision.”

Hard or soft Brexit? Schöldtz argues that the outcome is still unknown. He points out, “We are in the midst of waiting for the Brits to give us exactly how they want to handle the permanent agreement or permanent relationship with the European Union going forward, and I’m still hopeful that it will not be a limited approach.” But he agrees when Palacio observes that “divorces are always terrible” and that this one is even more so, since it was so completely unexpected. At best, she hopes for a middle ground between a harmonious and a confrontational Brexit, where the U.K. participates in areas like defense and intelligence in the same way that countries like Sweden are full-throated E.U. members, but opted out of the Euro.

Finally, no conversation about Europe’s future can be complete without speculating on the outcome of the U.S. election. As Schöldtz puts it, “There is a huge risk that the U.S. with a Trump 2 administration will go after the Europeans. That would be severely bad news for both us and them if that happens … because then Europe will start to think that we cannot rely on these people, on the Americans.”

In any event—hard or soft Brexit, Trump or Biden, coherence or confusion towards China—Europe and its leaders must urgently answer Palacio’s simple question:“Europe, what for? In the end, this is what is crucial. Europe, what for?”

Ana Palacio is the former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Spain and international lawyer specializing in international and European Union law. From 1994 to 2002, she was a member of the European Parliament, where she chaired the Legal Affairs and Internal Market as well as the Citizens Rights, Justice and Home Affairs Committees. Ana Palacio served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Spain (2002-2004) and was a member of the Spanish Parliament (2004-2006) where she chaired the Joint Committee of the two Houses for European Union Affairs. She has been Senior Vice-President and General Counsel of the World Bank Group and Secretary General of ICSID (2006-2008). Palacio has been a member of the Executive Committee and Senior Vice-President for International Affairs of AREVA (2008-2009) and served on the Council of State of Spain (2012-2018).

Ana Palacio is the former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Spain and international lawyer specializing in international and European Union law. From 1994 to 2002, she was a member of the European Parliament, where she chaired the Legal Affairs and Internal Market as well as the Citizens Rights, Justice and Home Affairs Committees. Ana Palacio served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Spain (2002-2004) and was a member of the Spanish Parliament (2004-2006) where she chaired the Joint Committee of the two Houses for European Union Affairs. She has been Senior Vice-President and General Counsel of the World Bank Group and Secretary General of ICSID (2006-2008). Palacio has been a member of the Executive Committee and Senior Vice-President for International Affairs of AREVA (2008-2009) and served on the Council of State of Spain (2012-2018).

Magnus Schöldtz is Senior Advisor at the Wallenberg Foundations AB, and a former Ambassador at the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. He has served in various diplomatic functions in relation to the EU and NATO and the Middle East. Ambassador Schöldtz also held positions within United Nations in Lebanon and Somalia, and the Swedish Armed Forces Headquarters.

Magnus Schöldtz is Senior Advisor at the Wallenberg Foundations AB, and a former Ambassador at the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. He has served in various diplomatic functions in relation to the EU and NATO and the Middle East. Ambassador Schöldtz also held positions within United Nations in Lebanon and Somalia, and the Swedish Armed Forces Headquarters.

He is Senior Advisor to Mr. Jacob Wallenberg, Chairman of Investor AB; Mr. Marcus Wallenberg, Chairman of SEB, Saab AB, and FAM and to Mr. Peter Wallenberg Jr. the Chairman of Wallenberg Foundations AB, as well as to several companies in the Wallenberg sphere.

In my culture there is a proverb: “Unity is Power”; to be powerful you have to unite. I wish the EU unity power and prosperity as important part of the world and good friends to my country Egypt ….