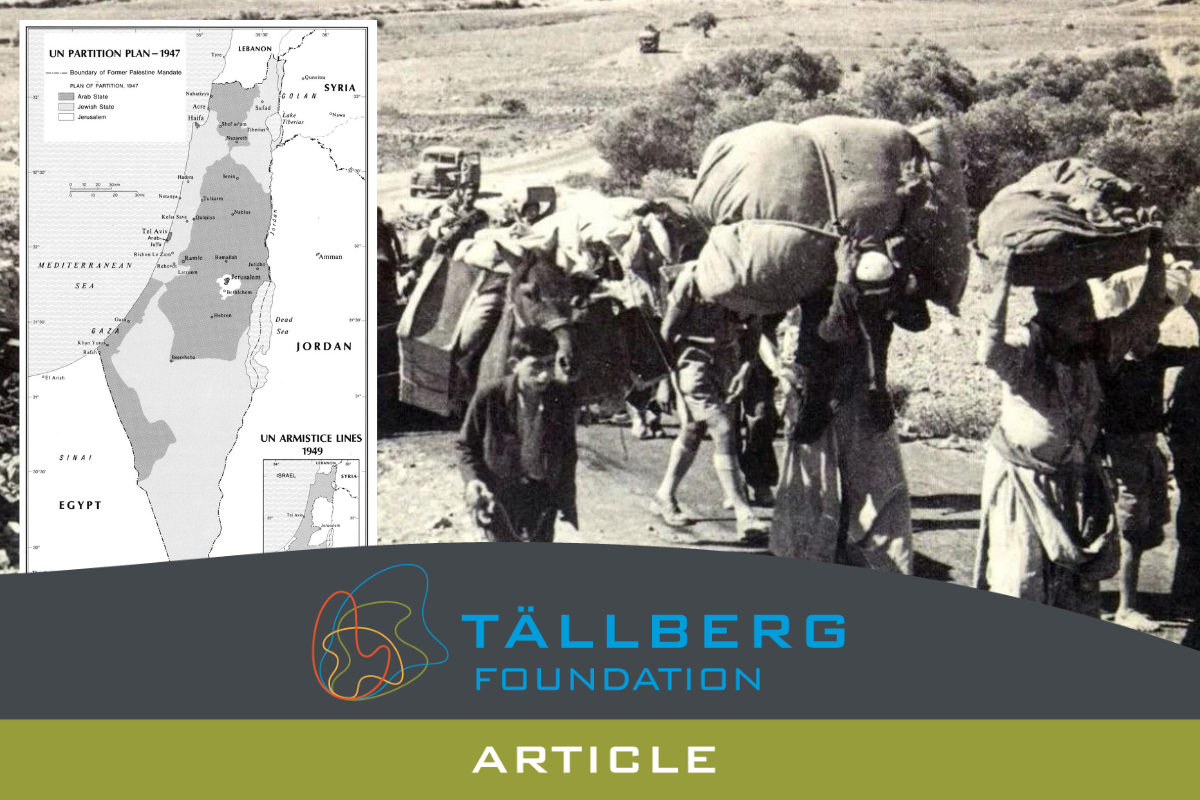

“Let us not cast blame on the murderers. For eight years, they have been sitting in the refugee camps in Gaza and before their eyes we have been transforming the lands and the villages where they and their fathers dwelt into our estates…Let us not be deterred from seeing the loathing that is inflaming and filling the lives of hundreds of thousands of Arabs living around us.”

Moshe Dayan, April 1956, eulogy for a murdered Israeli settler

The many Israelis who forgot Dayan’s prescient words amidst the prosperity of a modern, almost European state, were brutally reminded of them on October 7th. But does that brutal awakening foreshadow a national willingness to think differently about Gaza and the West Bank or will it deepen the evident unwillingness to negotiate a lasting settlement? Indeed, is a settlement even possible among people who have well-documented reasons to distrust and even hate each other? Could the Gaza war be the tipping point that forces Palestinians and Israelis to define a different future? Or will today’s violence and terror simply produce more violence and terror?

Two recent New Thinking for a New World podcasts point in different directions. Former Egyptian diplomat Nabil Fahmy argued, “[Diplomacy] is the only option we have if we want to stop the cycle of violence.” It’s fair to say that American journalist Armin Rosen seems skeptical that such an option exists: “I think what happened was so horrific, that there’s a sense across all of [Israeli] society that the group that did this can’t be allowed to survive, that it’s worth taking on great sacrifices to destroy it.”

Ironically, the very brutality of October 7 as well as the fact that Hamas has somehow survived seven months of Israeli assault might doom the diplomacy that Fahmy believes is critical. There seems to be almost no Israeli interest in a negotiation any bigger than hostages-for-ceasefire (which Fahmy points out makes little sense to Hamas if it wants to survive). According to Fahmy, “If this doesn’t become a larger issue for the world, the politicians on the ground will be unable to take strong decisions. We will end up having a series of ceasefires, low scale confrontations, and then major confrontations every now and then.”

At the same time, Rosen says, “People can ask whether October 7th was a success for Hamas…Hamas’s objective diplomatic status has improved: the Qataris did not kick them out; the Turks are more pro-Hamas than they have ever been; and the United States government is not immune from this either… [Hamas] has managed to create diplomatic facts that are very much in their favor despite October 7th and despite losing on the battlefield.” If that’s true, is there any possibility that Israel, having failed to destroy Hamas, would accept it as a negotiating partner—one that somehow has gained international legitimacy as a result of its terrorism?

Hard to believe, but Fahmy keeps his eyes fixed on the prize. “How do we stop this from happening again? The only way is to solve the problem…Violence breeds violence.” Fahmy, who spent much of his career dealing with failed Middle East peace attempts, proposes a comprehensive ten-point action plan that would be embedded in a new U.N. Security Council resolution:

- Ceasefire and the provision of humanitarian assistance;

- Exchange of Israeli hostages and Palestinians in Israeli prisons;

- Development of a security arrangement between Israel and the Palestinians to ensure non-use of force;

- Withdrawal of Israel from Gaza;

- International support for reconstruction and return of Palestinians;

- International recognition of a Palestinian state based on 1967 borders, including possible admission to the United Nations;

- Creation of a technocratic government among the Palestinian factions to govern Gaza and the West Bank;

- Call for elections both by Palestinians and Israelis in the next 12 months;

- Reaffirmation of the Beirut Summit Declaration which says that when there is a solution between Palestine and Israel there will be normal relations between Israel and all the Arab states;

- Establishment of the objective to negotiate a two-state solution within 24 months

Of course, the devil would be in the details, but the bigger question is whether Israel and the Palestinians have the bandwidth—and, perhaps, the courage—to embrace such a diplomatic and political “Everything, Everywhere All at Once” agenda?

Rosen would probably be skeptical. He argues that “The two-state solution remains a very specific kind of American idea, born out of the Western victory in the Cold War. It’s the idea that this is a unipolar world where things that seemed impossible are possible now and that the kind of inherent morality of American global leadership could bring about these massive shifts that people previously thought could never happen…[The two-state solution] is part of the catechism of the American elite.”

That might be right, but it begs the question whether the United States is still the indispensable nation in the search for Middle Eastern peace and prosperity as it has been since Henry Kissinger’s 1973 diplomacy. Now it is Fahmy’s turn to be skeptical. “America has moved from wanting to be a global power with the benefits and responsibilities, to being a superpower, which basically means [America is] stronger and richer than anybody else and can have influence without responsibility.” In effect, Fahmy argues that U.S. participation in a comprehensive effort is necessary but not sufficient. “I want the legitimacy of the U.N…I don’t believe that America alone is useful, but I don’t think that the Permanent Five [of the U.N. Security Council] without America works.”

Inherent in that view is the idea that the United States might no longer see its national interest as entirely coincident with Israel’s. Rosen certainly thinks that is the case, arguing not only that U.S. officials have effectively adopted some of Hamas’ negotiating positions, but that the U.S. forced Israel not to respond aggressively to the April 13th Iranian missile and drone attack. He says, “The [Iranian] regime figured out that they didn’t really need to make any concessions to the United States at all over the past 10 to 15 years, rather that they could create a reality in which the US could become its de facto protector against the Israelis.”

Washington would undoubtedly object to that assertion. However, everything that has happened since October 7th makes the case that, as Fahmy puts it, “The Middle East is being recalibrated.” His fear is that “if we recalibrate it into a mold where nation states don’t have credibility or authority, where non-state actors can express their anger because we can’t provide them with solutions, it’s going to be a very unstable situation.”

He could have added that instability in the Middle East rarely stays in the Middle East.

PODCAST EPISODES

Things Are Never So Bad They Can’t Get Worse…

Things Are Never So Bad They Can’t Get Worse…

In the wake of the violent October 7 events and the subsequent Israeli response in Gaza, the region faces a dire humanitarian crisis. Despite the bleak history of peace efforts, former Egyptian Foreign Minister Nabil Fahmy discusses the urgent need for renewed attempts to achieve lasting peace and prosperity for both Palestinians and Israelis. Join him as he explores potential paths to a peaceful future beyond the cycle of violence.

LISTEN HERE

War Lessons

War Lessons

The conflict between Hamas and Israel, which began with Hamas terrorists’ actions, has escalated into a wider war involving various factions and nations. Journalist Armin Rosen discusses the ongoing conflict’s impact on the Middle East’s political landscape, including questions about security, statehood for Palestinians, and the potential for broader regional conflict.

LISTEN HERE

ABOUT OUR GUESTS

Armin Rosen is a New York-based senior writer for Tablet Magazine. He has reported from across Europe, Africa, and the Middle East for a range of publications, including the New Republic, the Atlantic, and the Wall Street Journal. Before working at Tablet he was military and defense editor at Business Insider, where he received an International Reporting Project fellowship to fund a series of articles about Niger’s uranium industry. He has written dozens of essays and reported pieces for Tablet, including definitive profiles of Ilhan Omar and Israeli defense minister Yoav Gallant.

Nabil Fahmy, a career diplomat, served as Egypt’s Foreign Minister from July 2013 to June 2014, guiding the country’s diplomacy through challenging times. He reoriented Egypt’s foreign policy, broadening its options globally and regionally. Over three decades, Fahmy held prominent diplomatic roles including Ambassador to the United States and Japan. He chaired the UN advisory board on disarmament and was Vice-Chairman of the UN General Assembly’s first committee on disarmament and international security. He played key roles in various multilateral events and was honored by the Japanese Emperor. Fahmy founded the School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the American University in Cairo in 2009, serving as its dean until 2022. His latest English book, “Egypt’s Diplomacy in War, Peace, and Transition”(2020), and an updated Arabic book, “From the Heart of Events” (2022), shed light on the challenges of statecraft over the past fifty years.

The reflections on the potential outcomes of the Gaza conflict highlight the deeply entrenched complexities and the divergent viewpoints on achieving peace. Moshe Dayan’s poignant words from 1956 underscore the historical grievances and the profound emotional and social wounds that have shaped Israeli and Palestinian perceptions. The brutal events of October 7th have reignited these sentiments, raising questions about the future of diplomacy and the feasibility of a lasting settlement. Nabil Fahmy’s emphasis on diplomacy as the sole means to halt the cycle of violence suggests a comprehensive approach involving international cooperation and a broad-based plan for peace. His ten-point action plan addresses immediate humanitarian needs, security arrangements, and long-term political solutions, such as the establishment of a Palestinian state based on 1967 borders and a negotiated two-state solution. Fahmy’s vision implies that only a concerted global effort, with active participation from key international players including the U.S. and the U.N., can break the current impasse and provide a sustainable path forward. Armin Rosen’s skepticism about the viability of such diplomatic endeavors reflects a more cynical view of the current geopolitical landscape. His perspective points to the hardened Israeli stance post-October 7th and the strategic gains Hamas has made despite significant losses, suggesting that the chances for meaningful negotiations are slim. Rosen’s view highlights the challenge of reconciling the immediate security concerns of Israel with the broader diplomatic and political goals of peace advocates. The juxtaposition of these viewpoints raises critical questions about the future of Israeli-Palestinian relations. Can the international community muster the political will and resources to support a comprehensive peace initiative? Will the recent violence entrench positions further, making negotiations even more elusive? Or could it serve as a catalyst for a renewed commitment to peace, recognizing that the current trajectory only leads to more suffering and instability? Ultimately, the future hinges on whether the involved parties and the global community can find the courage and vision to pursue a path of reconciliation and coexistence, despite the daunting challenges and deep-seated mistrust. The hope for peace lies in the willingness to embrace diplomacy and compromise, acknowledging that while war can produce temporary victories, it rarely yields lasting peace.

I believe that to solve our problems, we should to bring it to discussion rather than war, so that we can agree on win win relationship.

Reading this, one gets the sense that this issue in the Middle East is both complicated and simple

It is the human element that is complicating the issues here and the stark unwillingness to build Trust through Truth and abide by laid down laws and precedents

Trust on all sides is conspicuously missing

The idea that war can produce peace is one of the most contentious and complex topics in international relations and conflict resolution. As Moshe Dayan’s 1956 eulogy poignantly highlights, the roots of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are deep, grounded in history, displacement, and mutual grievances. Dayan’s words resonate today, reflecting the enduring pain and resentment that continue to fuel the cycle of violence.

Historical Context and the Roots of Conflict

Dayan’s acknowledgment of the Palestinian experience—the transformation of their lands into Israeli estates and the resulting animosity—underscores a fundamental aspect of the conflict: both Israelis and Palestinians carry deeply entrenched narratives of suffering and loss. The displacement and subsequent refugee status of many Palestinians have been central to their national identity and their grievances against Israel. Conversely, the historical persecution of Jews and the existential threats faced by the state of Israel form a crucial part of the Israeli psyche.

The Impact of Violence and War

War, with its immediate human cost and long-term societal scars, rarely lays the groundwork for lasting peace. Instead, it often exacerbates existing tensions and engenders further hatred. The violence on October 7th, as a brutal reminder of Dayan’s words, likely intensified fear and animosity on both sides. Such incidents typically reinforce hardline positions, making the prospect of negotiation and reconciliation even more remote.

The Possibility of Peace Through War

Despite the grim realities, history provides some examples where conflict has led to peace, albeit often through protracted and painful processes. The peace processes in Northern Ireland and South Africa, for instance, emerged from violent conflicts but required significant shifts in political will and societal attitudes.

For peace to emerge from the Gaza conflict, several conditions would need to be met:

Mutual Recognition of Grievances: Both Israelis and Palestinians would need to acknowledge and empathize with each other’s historical and current suffering. This does not mean accepting each other’s narratives entirely but recognizing the legitimacy of the other’s pain.

Leadership Willing to Compromise: Effective and courageous leadership on both sides is crucial. Leaders must be willing to make difficult concessions and resist the pressures of hardline factions within their own communities.

International Support and Pressure: The international community can play a vital role in facilitating dialogue and providing guarantees for any agreements reached. This support must be balanced and aimed at fostering genuine reconciliation rather than merely imposing solutions.

Grassroots Movements for Peace: Sustainable peace often requires a groundswell of support from ordinary people who are tired of conflict and willing to work towards coexistence. Civil society initiatives can bridge divides and build trust from the ground up.

The Danger of Continued Violence

Without a concerted effort to address the underlying issues and foster dialogue, the violence in Gaza and elsewhere is likely to perpetuate a cycle of retaliation. Each act of terror and military response deepens mistrust and hatred, making a negotiated settlement more difficult.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while war is more likely to produce further violence and entrench hostilities, it can also act as a catalyst for change under the right conditions. The current conflict could push both sides to recognize the futility of continued violence and the necessity of dialogue and compromise. However, this requires a significant shift in attitudes and approaches, both among leaders and the general populace. The path to peace is fraught with challenges, but history shows that even the most entrenched conflicts can find resolution when there is a genuine commitment to reconciliation and a shared future.

Diplomacy dialogue is the way to go , to ensure peace is restored, when peace will be assured , other activities will occur gradually such us , hospitals opening, rebuilding of the city and live will be back

I have learnt about Sociology of Non-violent Change, war is not the way to go, and children are affected the most. As the Chief Executive Director of The Green Child International Organization, also serving as Chairman, Advancing Development in Africa for Africans LTD/GTE I call on both parties to seize fire. We need a world of peace for everyone anywhere.