Latin America is in trouble. From the Rio Grande to the Drake Passage, angry and violent partisanship is rising; citizens feel their governments have failed to provide peace, prosperity or security; courts and the media—the usual counter-balances to autocrats—are weakening; and too many politicians are proposing radical, rather than centrist, solutions.

So, what is the future of democracy in the Americas?

“Violence could be around the corner, but it does not mean that democracy will die,” insists Eduardo Amadeo, an Argentine economist, diplomat and politician. Indeed, says Colombian risk expert Sergio Guzmán, “The cry in the streets is not for less democracy, but for more democracy, for more participation, for more involvement in the government’s decisions and for the government to be more transparent and to consult with people more.”

American politician Tip O’Neill famously insisted that all politics is local. Patricio Navia, a leading Chilean social scientist, argues that what has happened in Chile over the past two years makes the case. ”People did go out to the street. They wanted more equality; they wanted more social services, more social rights. And the response the [Chilean] political class gave them was, ‘Okay. So, rewrite the rules of the game rather than increase social expenditure, rather than increase social rights… rewrite the whole constitution.” But Navia worries that the elite might have outsmarted themselves if the soon-to-start popularly elected constitutional convention in Chile rewrites the rule in ways “that might end up leaving everyone worse off.”

That’s the dilemma; as Amadeo puts it, “what sort of democracy are we going to have: a democratic regime or just elections?” Navio speculates that democracy might be “a pleasure that only the wealthy can afford to have; for the poor, satisfying immediate needs might be way more important than democracy.”

“Immediate needs” seems to be a placeholder for “social contract” between citizens and their elected leaders—which is exactly the problem in too many countries. “What we’ve seen in many places in Latin America is the state’s complete inability to keep its populations alive,” says Guzmán. “The rich have already gone to New York, to Miami, or to Texas for their vaccinations while the poor are stuck with a social contract that they have no way of changing.”

That is certainly the case in Argentina, according to Amadeo: “The social contract in Argentina has to be rewritten and some of the basic values that let a society work should be rediscussed. For example, populism in Argentina has always prioritized the present to the future and the result of that is inflation… So the chances that Argentina falls into a process with terrible uncertainty in terms of violence, economy, poverty, et cetera, are very high. What’s going to be the social contract after that?”

Navia summarizes, “If there are just way too many people with nothing to lose, then you are not going to have strong support for democratic systems in Latin America.” The antidote? If you can create a strong enough middle class, that middle class will be the basis on which you can build democracy.

Saying it is easier than doing it, especially with a pandemic still raging and a complicated global economic situation where multilateralism is under pressure. “In Colombia” says Guzmán, “the pandemic made all the social tensions that we had prior worse. Unemployment is worse, people not working and not studying have increased significantly. Inequality has grown quite significantly as well.” And the government’s failure so far to provide vaccinations “touches people very personally…[even] their ability to survive.”

Navia agrees, but adds a positive twist. Because of the pandemic and its aftermath, he observes “We’re going to see higher levels of inequality in a region that was already very unequal. Pandemics are going to worsen the situation, but they also provide a great opportunity for both those interested in promoting democracy and those interested in promoting equality.”

Unfortunately, it’s also a risk, as he explains, “If those needs are satisfied by an authoritarian leader who might be elected democratically…then people are going to be happy with that leader.” So, how to find good leaders who are competent and democratic?

Amadeo worries, “There are enormous incentives to be non-efficient, to say the least, or corrupt. Unless we can end corruption in Argentina, it’s going to be hard to have good leaders because a number of politicians are attracted by the possibility of getting rich very fast.” Navia argues that the answer is not a Diogenes-like search for honest leaders: “If you put the right incentives in place, then even bad politicians will behave properly.” His list: “You have to pay politicians well. If you do not pay politicians well, they will find other sources of income and that’s precisely what we don’t want them to do. You also have to allow for their reelection. They have to be allowed to develop political careers.”

Admitting that better pay for politicians is unlikely to be popular, Navia underscores the need for professionalism in politics. “You don’t want somebody to be your doctor for four years and then go do something else, right? You want somebody to be a good doctor for many, many years. And, in fact, you should think of politicians as doctors and political parties as hospitals…I think we’re moving in the opposite direction by getting this idea that anybody can be a politician, and it’s just a matter of getting somebody from the outside and letting that person lead the country. We are getting ourselves into a really, really bad situation.”

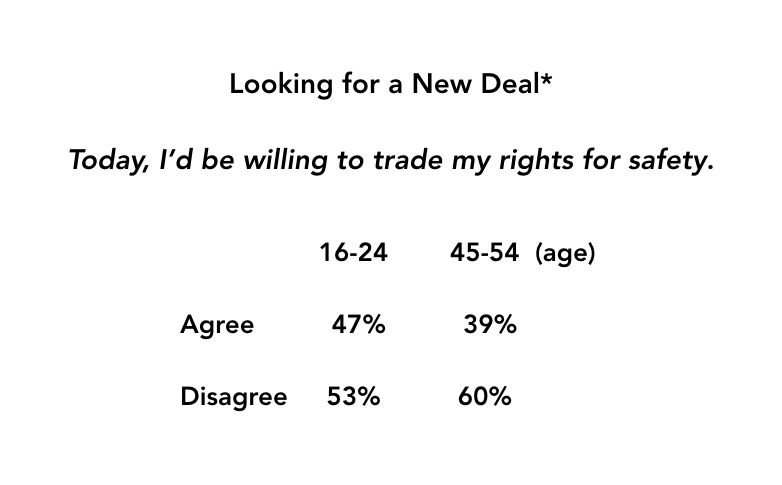

That perception matters at a time when 45% of respondents to a region-wide poll last fall said they would be willing to trade their rights for safety and only 60% said that democracy is preferable to any other form of government.* And the data is clear that young people in particular are skeptical of democracy and more willing than their parents to make the hypothetical trade—which is not so hypothetical in the rhetoric of many politicians.

That youthful skepticism does not surprise Guzmán. “A lot of young people particularly feel frustrated with the system, feel frustrated with the system that the previous generation left them,” he says. “They feel upset that there’s corruption, that there’s infrastructure deficiencies, that there’s education deficiencies. They need positive routes to channel their energy.”

That, perhaps, is the good news. Democracy, Guzmán insists, “is being requested and demanded in the form of accountability, institutional presence, and—why not—responsibility.”

Why not, indeed?

****************

* “Perceptions of Democracy in Latin America during COVID-19,” Luminate, 2020

Let us know what YOU think and comment below

Eduardo Amadeo, Sergio Guzmán and Patricio Navia recently spoke with Alan Stoga as part of the Tällberg Foundation’s “New Thinking for a New World” podcast series. Hear their whole conversation here or find us on a podcast platform of your choice (Apple Podcast, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher, Libsyn, etc).

ABOUT OUR GUESTS

Eduardo Amadeo has served his country in many capacities, most recently (2015-19) as an elected member of the national Congress, representing Buenos Aires as a member of the Propuesta Republicana formed by President Macri. During his mandate he served as Chairman of the Finance Committee.

Eduardo Amadeo has served his country in many capacities, most recently (2015-19) as an elected member of the national Congress, representing Buenos Aires as a member of the Propuesta Republicana formed by President Macri. During his mandate he served as Chairman of the Finance Committee.

Previously, he was President of the Bank of the Province of Buenos Aires (1987-91), Secretary for Social Development of the Republic of Argentina (1994-98) and Ambassador to the United States (2002-3).

In addition, he was deputy chief of the Cabinet of Ministers and spokesperson for President Eduardo Duhalde. As Secretary for the Prevention of Drug Addiction and Control of Drug Trafficking (1998), he implemented the first comprehensive statistical system for drug demand in the country. In 1994, he became a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

He was first elected to Congress in 1991, where he became president of the education committee and secured the approval of the federal education law and the law for superior education.

Sergio Guzmán is the Director of Colombia Risk Analysis. He provides commercial, security, and political risk analysis for the Andean region. His expertise is in the Colombian conflict, the resolution of international conflicts, and international development. Before joining Colombia Risk Analysis, Sergio was the principal analyst for Colombia, Bolivia, and Suriname at Control Risks where he was an international consultant in political and security risks.

Sergio Guzmán is the Director of Colombia Risk Analysis. He provides commercial, security, and political risk analysis for the Andean region. His expertise is in the Colombian conflict, the resolution of international conflicts, and international development. Before joining Colombia Risk Analysis, Sergio was the principal analyst for Colombia, Bolivia, and Suriname at Control Risks where he was an international consultant in political and security risks.

Sergio holds a Master’s degree in International Economics and International Relations from the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University. His native language is Spanish, he is fluent in English and is proficient in Portuguese. Sergio has spoken at numerous regional and international conferences on issues of political economy, finance, anti-corruption, and international relations.

Patricio Navia is a full professor of political science at Universidad Diego Portales in Chile and a clinical professor of liberal studies at New York University. He is also affiliated to the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at NYU. He holds a Ph.D. in Politics from NYU and an M.A. in political science from the University of Chicago. He regularly writes on elections, public opinion, political parties, legislatures and democratization in Chile and other Latin American countries. He is a regular columnist at the Americas Quarterly and El Libero (Chile).

Patricio Navia is a full professor of political science at Universidad Diego Portales in Chile and a clinical professor of liberal studies at New York University. He is also affiliated to the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at NYU. He holds a Ph.D. in Politics from NYU and an M.A. in political science from the University of Chicago. He regularly writes on elections, public opinion, political parties, legislatures and democratization in Chile and other Latin American countries. He is a regular columnist at the Americas Quarterly and El Libero (Chile).

Sub: Covid -19 suffered to Local poor and poorest woman’s family’s nutrition’s & Income Generate Business Model of marketing value change Idea in Bangladesh.

Dear Sir,

Greeting form Unique Agro Services center, Jhenidah Bangladesh.

The Unique Agro Services center works in villages woman poor and poorest families. These families’ major problems areas: (Rural women, children and pregnant women, Adlocentess including families law of nutrition’s, each family’s medical and medical costs have increased, Physical weakness is losing, The source of income for the family has decreased)

The Unique Agro Services center small level Solution activities works: (Supplies of Jiending ducks -20 paces per Family, chickens -20 paces per Family, Supplies of the Moringa tree-10 paces pre Family, Supplies high quality vegetable seeds-5 items per Family, skill Training women farmers)

The Business Model: (Total agro kinds Production items 50% mast be own/ Family members eating and 50% Purchase of Unique Agro Services center. this project is village level very demined and very Successful

I hope the Unique Agro Services center by being able to meet the financial needs of the family by selling the products produced. I believe you could visit this small project on my own. I am implementing the project by involving a total of 720 woman’s families under this service. I demand more technical value creation and technical support from you.

Note: Members of SUN Business Networking, GAIN and WFP Bangladesh.

Thanks.

M.Anamul Haque Milon

Managing Director

Unique Agro Services center

Jhenidah District, Bangladesh.

Mobile: +88 01725215568

E-mail: milon79@yahoo.com

Diagnoses are relatively easy to make, but solutions are far more difficult as demonstrated by the paucity offered by the writers. One solution (Navia) appears to be paying better to the politicians; that is contradicted by the Chilean experience where members of the parliament are extremely well paid, and yet, they have contributed next to nothing in terms of positive initiatives. Furthermore, any and all solutions are medium- to long-term, whereas needs for more equality, etc are immediate. It is a sad illusion that a reform of the constitution (mid-term to long-term is follow up laws are considered) will contribute to solving current problems. The situation in LAC may therefore lead to the appearance of illuminated “saviors”, and similar fauna.