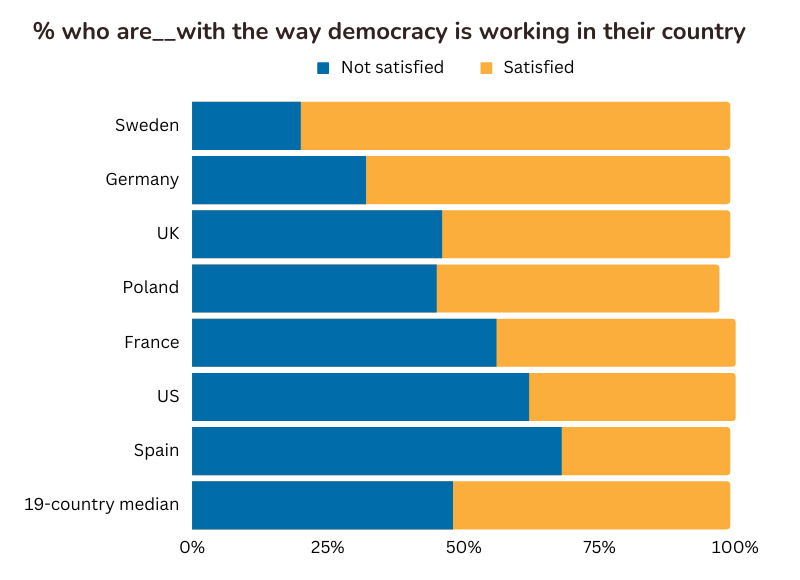

In an opinion poll of 19 mostly Western democracies conducted last year, almost half of respondents said they were dissatisfied with how democracy works in their country—including 62% in the United States, the self-declared “leader of the free world.” What’s wrong? Is it the people, the leaders, the outcomes, the processes—or all of the above?

Source: PEW RESEARCH CENTER, DECEMBER 5, 2022 Note: Those who did not answer not shown. Median is Sweden, Singapore, Germany, Netherlands, Australia, Canada, UK, Belgium, Poland, Malaysia, South Korea, Israel, Hungary, France, Japan, US, Italy, Greece, Spain.

Elisabeth Braw, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, seems focused on the first of that list: we, the people. As she argued in a recent New Thinking for a New World podcast, “Those of us living in liberal democracies—those of us who have never experienced any other form of society—we take liberal democracy for granted. We just assume it will always be around, because that’s the only way of life we know. But there is nothing guaranteed about liberal democracy. It requires everybody to pitch in to help maintain it, because otherwise it will collapse under the pressure, burden, and attacks of those who hate democracy.”

That’s an important point, but not a unique argument. What is at least unusual about Braw’s framing is her point of departure: a book written by Austrian philosopher Karl Popper, begun in 1938 and finished in 1945. “The Open Society and Its Enemies” was Popper’s reaction to Hitler and his abuse of Germany’s democratic system to seize power.

As Braw recalled, Popper formulated the paradox of tolerance when he wrote:

Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. – Karl Popper, Open Society and its Enemies

That raises an obvious question and a huge dilemma. As Braw puts it, “At what point do you have to become intolerant? If you attack somebody in the name of ideology, you are prosecuted for it. But if you criticize that person, you don’t go to jail because we have freedom of speech. But, what we are seeing today is that you can do so much harm to society at large by exploiting that freedom….if there are elements of society that are willing to engage in very provocative acts and indeed trigger violence through their words and through their actions—even if they don’t physically attack anybody—then we have to start entertaining the notion that we should be less tolerant of radical views simply because liberal democracy is not guaranteed to exist.”

Albeit cautiously, Braw echoes Popper:

As long as we can counter them [intolerant philosophies] by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be unwise. But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument… We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places Itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal. – Karl Popper, Open Society and its Enemies

All of this is not a theoretical exercise; Braw is deeply concerned about developments this past summer in Sweden which led that country to fear increased Islamic terrorism in reaction to several instances of public Koran desecrations.

That story began with Sweden’s decision to join NATO and the consequent need for Turkey’s acquiescence. But Turkey’s President Erdogan drove a hard bargain, including a demand for the repatriation of Turkish Kurds who live in Sweden and are protected by Swedish law. The Swedes and Turks were (and still are) at a stalemate, which made Sweden vulnerable to incidents that might inflame Muslim—including Turkish—public opinion. A couple of provocateurs took advantage of the opportunity to desecrate Korans in public events protected by Sweden’s deep commitment to freedom of speech, deplored by Swedish authorities who had no legal right to intervene.

The results included “a massive disinformation campaign against Sweden, propagated primarily by Arabic and Russian language accounts on social media; condemnation by the governments of Iran, Iraq, and a few other countries; attacks on the Swedish embassy in Baghdad; and massive Muslim anger against Sweden,” says Braw. In addition, Sweden’s Security Service was forced to raise its assessment of the level of terrorism threat against the country and, according to Prime Minister Kristersson, succeeded in deflecting several specific attacks.

But all of that, insists Braw, was based on deliberate misinformation since the Swedish government does not support Quran burnings, but lacks the right to ban them. And that’s the double bind: to meet the demands of the Muslim protestors to stop what is (reluctantly) protected action in Sweden would mean changing the Swedish laws that protect free speech. A slippery slope: defending democracy by curtailing democracy.

Braw suspects it might even be worse. “Now if Sweden does changes legislation, it sends a message to the world that if you attack verbally and perhaps physically a liberal democracy strongly enough that liberal democracy will say ‘This is uncomfortable. We better compromise so that it doesn’t happen again.’ Of course, if you send that message as a liberal democracy, the side that is willing to engage in aggression against you will do even more of it.” Indeed, she worries that if only liberal democracies are tolerant, “the other side doesn’t make concessions” and the slippery slope leads towards disaster.

The unfair question is whether what Braw describes is embedded in a clash of civilizations or religions and, hence, unique to the interactions between people of different cultures or worldviews or belief systems. No, she insists, “This is a clash between those wanting to live in a tolerant way, and those who, for whatever reason, are keen to exploit that [tolerance] and use it for harm.”

If that’s right, might it apply to the harsh, divisive, extremes-driven version of American politics that has become that country’s new normal? Braw worries that it could be. “I’ve lived in America on and off since 1996, and…I’ve seen American society go from mostly friendly with people willing to engage with people of all political persuasions to this hyper-partisan environment.” She blames the transformation partly on the nature and abuse of social media and partly on a breakdown of traditional American social institutions that used to cut across party and class lines. The combination contributes to information bubbles, tunnel vision, and “in the most extreme of cases, involvement in conspiracy theories, which was obviously what triggered the January 6th attack on the Capitol.”

Does such a world sound too much like the one Popper was observing when he reflected on how the Nazis had undermined liberal democracies in the 1930s? If so, how to preserve our democracies? Where to draw the line on intolerance? “I think the moment you have free speech that incites violence… that’s where you have to draw the line. We can have any number or manner of ugly opinions; we can allow those to exist within our societies and be expressed within our societies.” But, she insists, “opinions that incite violence [should be] the red line to draw for what we can permit within our societies while remaining tolerant.”

Exactly what Karl Popper had in mind when he wrote about “the paradox of tolerance.”

***

What do you think? Let us know by commenting below

***

Elisabeth Braw recently spoke with Alan Stoga as part of the Tällberg Foundation’s “New Thinking for a New World” podcast series. Listen to their conversation here or find us on a podcast platform of your choice (Apple podcast, Spotify, Google podcast, Youtube, etc).

ABOUT THE GUEST

Elisabeth Braw is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where she focuses on defense against grayzone threats. She is also a columnist with Foreign Policy and Politico Europe, where she writes on national security and the globalized economy, and the author of The Defender’s Dilemma: Identifying and Deterring Grayzone Aggression (2022). Elisabeth is a member of GALLOS Technologies’ advisory board, a member of the UK National Preparedness Commission, an adviser to Willis Towers Watson’s research arm and a member of the steering committee of the Aurora Forum (the UK-Nordic-Baltic leader conference).

Elisabeth Braw is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where she focuses on defense against grayzone threats. She is also a columnist with Foreign Policy and Politico Europe, where she writes on national security and the globalized economy, and the author of The Defender’s Dilemma: Identifying and Deterring Grayzone Aggression (2022). Elisabeth is a member of GALLOS Technologies’ advisory board, a member of the UK National Preparedness Commission, an adviser to Willis Towers Watson’s research arm and a member of the steering committee of the Aurora Forum (the UK-Nordic-Baltic leader conference).

Elisabeth’s book Goodbye, Globalization: the Return of a Divided World will be published by Yale University Press in the new year. She regularly writes op-eds for the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Times and (writing in German) the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and is also the author of God’s Spies, about the Stasi (2019). Elisabeth attended university in Germany, graduating with a Magister Artium in political science and German literature.

0 Comments