Those words have not been spoken by many this year. But Jorge Castañeda—Mexican educator, diplomat, former Foreign Minister, and frequent critic of the United States—believes that all the turmoil of a mishandled pandemic, economic recession, racial unrest, extreme political partisanship, and palpable anger throughout society might just be providing the impetus the country needs to have a better future.

It is promising, Castañeda says, because of “the United States’ incredible capacity to reinvent itself, to find new ways to address problems, some of which are new and some of which are not new.”

Castañeda, who has a lifetime of experience with all things American, reads the current political mood as showing not only the desire to change presidents, but to change the foundational structures of the country. “It’s not a question of just winning or losing [in November]. It’s about doing a whole bunch of things, including finally creating some kind of American welfare state, which the U.S. didn’t need before because it was sort of born as a middle-class society—except for everybody who wasn’t part of that middle-class society: the Native Americans, slaves, and later, the African Americans, the Latinos, and the Asian Americans.”

He sees strong popular support for higher minimum wages, universal healthcare, universal childcare, free public higher education, gun control, prison reform, and a bolder approach to climate change. He admits that none of this was particularly popular when the middle class was growing and wealthy, but he argues the last decades have changed everything as wages, opportunities, and mobility stagnated. But now large majorities, according to the pollsters, want the trappings and security of a modern welfare state.

Castañeda describes this as part of a process whereby the United States is becoming more like other modern rich countries. “American exceptionalism: some people like it, some don’t, but what remains of it is going to begin to fade away.” For example, “If you ask Americans how religious they are, they all say they’re immensely religious. … If you look at what Americans do … you increasingly see how Americans are beginning to look religious-wise a lot like Western Europe; that is, very unreligious. If you ask them, they say no. If you look at the numbers, they’re lying.”

And, he argues, if Americans become more like Europeans, they will almost inevitably adopt similar social policies, sooner or later. America’s growing, shared vision is not a certainty, but it is a source of hope. “It (reform) may fade away. It may not turn into legislation. It may not happen,” Castañeda admits. “But I certainly see the support there both in terms of candidates proposing this stuff and American public opinion supporting this stuff, at least for the moment.”

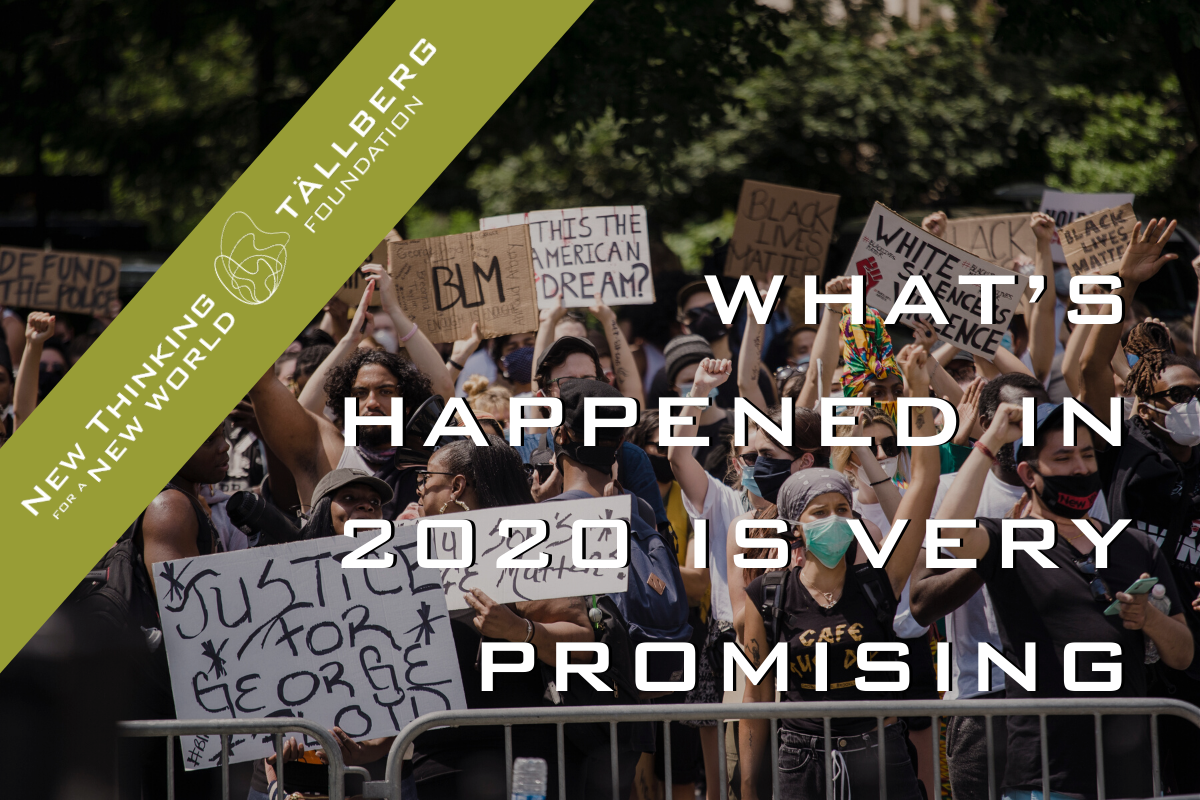

The list of needed changes, of course, includes race. “Despite the progress since the early and mid-sixties and despite very important things that have been done, it’s obvious that much more has to be done,” Castañeda says, “and probably you can’t do it without part of that welfare state being for African Americans.”

He believes the desire for deep change extends well beyond the usual suspects on both coasts. He offers the example of the Electoral College, which chose two recent Republicans presidents, despite their having lost the popular vote. For all practical purposes, the votes of individual citizens in deep red states like Texas or Kansas (as well as blue states like California or New York) have been irrelevant for decades. “Maybe Texans want their votes to matter now,” which could lead to replacing the Electoral College with direct, popular presidential elections, a heretofore almost unimaginable Constitutional reform.

All of this will take leadership, and Castañeda admits the landscape appears bleak. But, he points to two major moments of American reform: President Roosevelt’s New Deal and President Johnson’s domestic reforms. The former started as a president who was despised by prominent liberals; the latter was a Southern Democrat whose legislative track record was anything but progressive. Castañeda says, “I certainly wouldn’t imagine Joe Biden to be the ideal person for this, but Johnson wasn’t either.”

The key is context. “Leadership doesn’t necessarily shine until it does things, when it’s pushed by the streets, the universities, the pundits, the polls, and people who vote,” Castañeda says. He adds, “Radicalism is necessary in the United States in order for the reformists to be able to do things. There are no American reformists without American revolutionaries.”

Do either of those—reforming leaders or dynamic revolutionaries—exist today? “They may emerge,” Castañeda says. Although he admits he cannot name a modern version of Martin Luther King or Malcom X—or, for that matter, FDR or any other successful reformer.

However, what exists today and is a potentially powerful reforming force is “a real reaction against many of the things that had occurred during the Obama years, and even since the early ‘90s, among a section of the United States electorate that wanted something different on immigration, on trade, on the welfare state, as they perceive it to exist—which I think we know doesn’t exist, but they think it does—that the system is rigged in favor of the underprivileged and against them.” Castañeda adds, “My sense was that these were people who were saying, ‘Look, we want something different from what we have, because we haven’t gotten a great deal.’ I think they were looking for … the wrong solution to real problems and real challenges that existed. But I also think that none of what Trump has done has made life any better for any of these people who voted for him.”

He argues that the frustrated Trump voter wants some of the same things the frustrated progressives want: a welfare state that lets them live their own version of the American Dream. And Castañeda believes they will get it, if not in 2020, then in 2024. “I think that the United States over the next 10 years … will put together the kind of changes, the kind of coalitions that are necessary for those changes, electorally, legislatively, in terms of public opinion even, in terms of the cultural wars.”

That vision seems impossibly distant from crowds pulling down statues of Andrew Jackson or Christopher Columbus or removing Woodrow Wilson’s name from a school at Princeton. The cynic—or, perhaps, optimist—in Castañeda believes some elements of the cancel culture might prove to be positive. Foreigners, he says, accuse the United States “of not having a sense of history, of always looking to the future, not to the past, of not caring too much about history, not reading it, not studying it, not bothering with it … I think that it’s a good thing that Americans are finally arguing about history and realizing how important it is, even if that is done through things like trying to tear down Andrew Jackson’s statue in front of the White House.”

“That may not be the best way to get to history as an important issue, but it’s as good as any other, and if that works…

Jorge Castañeda recently spoke with Alan Stoga as part of the Tällberg Foundation’s “New Thinking for a New World” podcast series. Hear their conversation at, tallbergfoundation.org/podcasts/ or find us on a podcast platform of your choice, (Itunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher, Libsyn, etc)

Castañeda’s most recent book is America Through Foreign Eyes is available through Oxford University Press.

0 Comments