“We have a neighbor who is important, big, but still very aggressive, very assertive, and looking for adventures.”

“Erdoğan wants to dictate the terms of the game.” —Constantinos Filis

A weird year threatens to become even weirder: war between Turkey and Greece, two NATO allies with a long, fraught history, has suddenly become a possibility. To repeat: In 2020—not 1897, not 1920—there could be war between Turkey and Greece—something that should be unimaginable, even in this year of the plague.

In a New Thinking for a New World podcast, Constantinos Filis, a leading Greek foreign policy expert, asserted that “Turkey is exercising coercive diplomacy and wants to impose its will on other states in the region.” Although Filis thinks and hopes that war will not happen, “we should prepare ourselves for any scenario, even the worst-case scenario.”

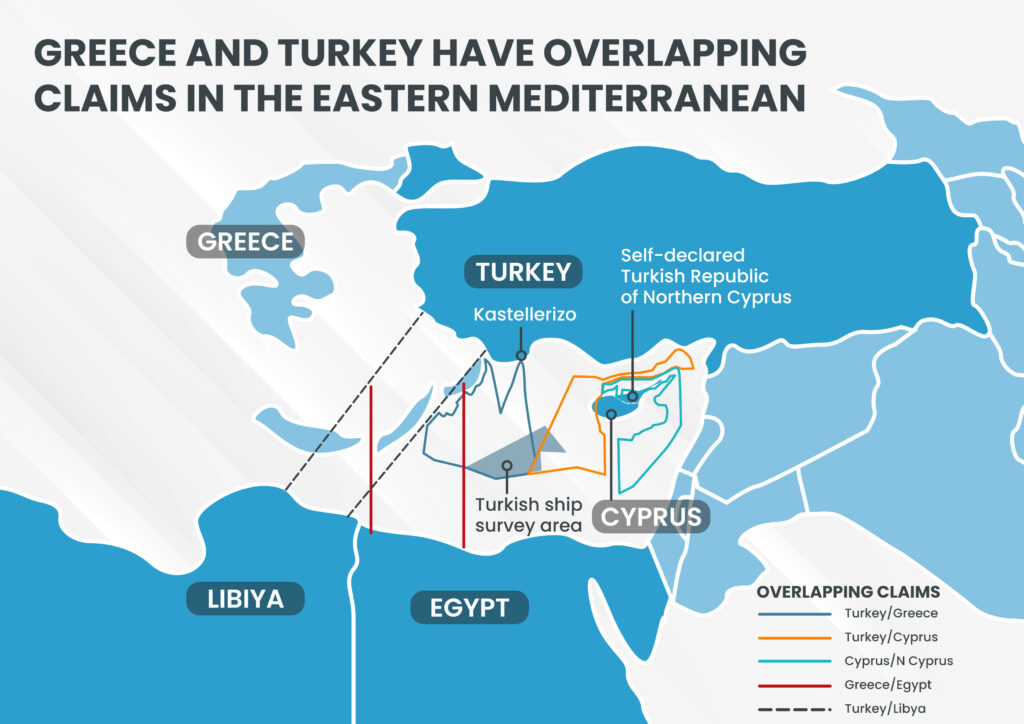

The immediate problem is a confrontation over potentially massive natural gas deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean. In the grab for gas, Greece has aligned itself with Cyprus and Egypt, while Turkey has partnered with Libya and Malta. They have two sets of overlapping maps, two sets of legal claims, two conflicting narratives about history and rights—and two flotillas of research vessels and warships that have already literally bumped into each other.

But Filis thinks the growing tension is more about the ambitions of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan than about hydrocarbons. “He doesn’t necessarily want to conquer the territory of a third country, be it Greece or Cyprus, although Turkey has already conquered almost one third of Cyprus,” Filis says. Rather, his goal is “to extend Ankara’s influence to a geographical range that resembles that of the Ottoman Empire.”

Filis’ list of grievances against Turkey is long. “Turkey is marginalizing itself from regional developments,” he says. “Turkey has very poor relations with both Israel and Egypt. Turkey does not recognize Cyprus. Turkey disputes and challenges Greece’s sovereign rights in a very consistent way. Turkey has been an aggressive participant in the Libyan and the Syrian wars” and has often breached international alliances and agreements along the way. He accuses Turkey of “fabricating its own admixture of interpretations and case law” in order to bend international treaties to its own desires and, in the process, wear down Greece and try to strip it of its sovereignty. Filis asserts: “It’s not Greece to blame for Turkey feeling or being actually marginalized from regional affairs. It’s more the Turkish leadership.”

Although Greece is deeply committed to the European Union and has a longstanding alliance with both the United States and, more generally, multilateralism, Filis is deeply critical of the lack of support the country has received from its partners. Despite Turkey’s expansionist, Ottoman Empire-like aggression, “we have a vacuum … after the U.S. decided to not to deal with everyday affairs of the wider region. … [The] E.U.’s and U.S.’s inaction whets Erdoğan’s appetite.”

Although Filis is skeptical that American policy will change before a new president takes office, he urgently wants Europe to start using carrots as well as sticks to shape Erdoğan’s behavior. The carrots could be increased direct investment, improved trade relations, and other economic incentives, while the biggest stick—in addition to a strong military deterrent—should be financial sanctions. However, because of German caution to even talk about sanctions, “we cannot tell whether President Erdoğan is bluffing when he says that he will go till the end in order to protect his country’s interests.”

The danger, Filis argues, is that the Eastern Mediterranean is too critical and too complex to be left to its own fate. He sees both Russia and China actively expanding their influence, which is antithetical to European and American interests. At the same time, Jihadist terrorism as well as renewed, massive migration are growing threats as long as the Libyan and Syrian crises remain unresolved. Failing or dysfunctional states and the after effects of the Covid-19 pandemic add to the witches’ brew. The resulting risks are enormous and could worsen: “If for instance, Egypt fails,” Filis says, “we will have a huge black hole at this part of the world.”

In that context, he insists that, “Greece must persuade its partners that what is happening and what will happen in the Eastern Mediterranean is not only a part of Greece’s national interests … or [those of] other regional powers, it is to the interest of the West as a whole.”

At the end of the day, Filis recognizes that, if Turkey is a large part of the problem, it must be a large part of the solution: “Greece wants Turkey to be part of regional developments and to be part of energy developments. We do realize that Turkey’s market is too big to be ignored, and that Turkey of course, if it decides to play a more constructive role in regional affairs, can and should be a market of great interest for all producers in the region.”

There is a balance to be struck, if both parties are willing. “Greece wants a dialogue with Turkey … obviously in the context of a special relationship with specific commitments and terms, that include good neighborly relations,” he says. “We cannot be stable and prosperous with Turkey playing that unproductive role.”

However, Turkey seems to be aggressively pursuing a different, deeply dangerous direction. The next weeks and months will be crucial, Filis believes, to finding some kind of equilibrium—or not. He hopes that Erdoğan understands “it’s not that easy for Turkey to start a war or even a short military conflict with us.”

But what he really seems to mean is that it would not be so easy for Erdoğan to win such a conflict.

Constantinos Filis recently spoke with Alan Stoga as part of the Tällberg Foundation’s “New Thinking for a New World” podcast series. Hear their whole conversation at below or find us on a podcast platform of your choice (Itunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher, Libsyn).

Dr Constantinos Filis is Director of Research at the Institute of International Relations of Panteion University. He is head of the Russia-Eurasia & SE Europe Centre at the Institute of International Relations since 2005.

Dr Constantinos Filis is Director of Research at the Institute of International Relations of Panteion University. He is head of the Russia-Eurasia & SE Europe Centre at the Institute of International Relations since 2005.

He was elected Senior Associate Member at St Antony’s College, Oxford University for two years (2007-2009). He has conducted a number of studies and advised international and Greek corporations. He is an active contributor to public debate in Greece and abroad. He is member of the Greek-Turkish Forum, as well as the Greek-Russian Society and Director of the International Olympic Truce Centre.

He recently finished a book on EU, migration and security (Papadopoulos publ.).

I think Constantine Filis, a foreign policy expert, has a very shallow analysis. His explanation didn’t reflect to his tittle.

Has Turkey, in current decade, been a destroying other countries with big agenda behind like US to Vietnam and Iraq? Like Israel to land and people of Palestine? The answer is a big NO

This “expert” is simply phobia to Ottoman empire which is actually no longer exists. Maybe because of his name is “Constantine”?

Greek is way behind Turkey in term of economy and technology and maybe many other things. His statement on Turkey seems to get sympathy from Western world or trying to be a trigger of anything bad, like race and religion discrimination or even a war!

Mr. Constantine (the not-great) please make a better analysis and objective on discussion. Expert who hasn’t been an advisor should be scientifically neutral, unless you have been a Greece government advisor…

I believe Turkey should restrain its actions as it know that shelf belongs to greece

Talking Peace instead. The game is dangerous and this is not the age of war ….