Sudan is at war with itself. Since the 2019 uprising that booted Omar al-Bashir from office after thirty years, the country has experienced more coups and fighting than democracy and peace. Indeed, as Sudanese activist Samah Salman points out in a recent New Thinking for a New World podcast, “We have a history in Sudan of 67 years of independence, fifty-four out of those ruled by dictators and autocrats.

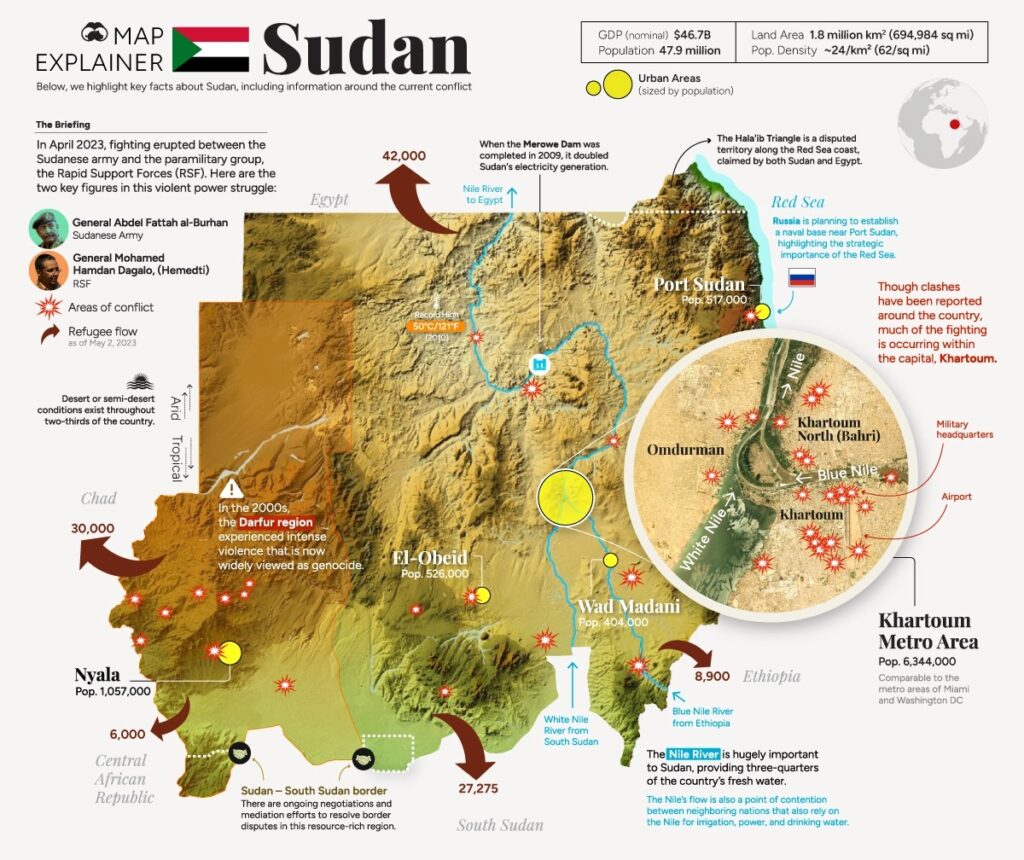

And now, two more of those would-be dictators are “locked in mortal combat for power and wealth. On the one hand, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of the Sudanese Army, and on the other, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo of the Rapid Support Forces…What they both want is power and wealth…that either one of them—both of them being creations of Omar al-Bashir—could actually want democracy is very farfetched,” she insists.

The irony is that the deadly rivalry of Generals al-Burhan and Dagalo (who is better known by his nickname, Hemedti) was made possible by the revolution that ended al-Bashir’s reign. Although both were senior military men during the Bashir regime, in April 2019, with thousands of people in Khartoum’s streets, “Hemedti changed the palace guards one night and in the morning arrested al-Bashir. So, ultimately what you had was a revolution that ended with a palace coup. Hemedti and Burhan, head of the Sudanese army, came in and actually took advantage of the revolution to say ‘Bashir is so weak and the people have all risen up against him, this is our opportunity to take power.”

In this tale worthy of Shakespeare, it’s important to understand that Hemedti, a former camel trader, was created by al-Bashir to build a militia to fight his war in Darfur. Eventually, that militia—the notorious Janjaweed—was transformed by Hemedti into a full-fledged army, christened the Rapid Support Force. Salman points out that, “No country in the world that has two armies. The fact that we do means that each…is trying to crush the other.”

It also has meant seemingly endless rounds of political instability. First, a civilian-military power sharing agreement that promised transition to democracy, followed by coups, conflict and international negotiations that produced a new framework agreement at the end of last year that, again, was supposed to lead toward democracy. Instead, it led to civil war that, in effect, is “a personal disagreement between two men as to who heads the country’s legitimate army…Each of the generals thinks that they can win. They’re locked in a fight in which the balance of power is very close. They have destroyed so much of Sudan and Khartoum that at this stage, they’re willing to destroy each other.”

Add one more actor to this witches’ brew: Omar al-Bashir’s Islamists and, perhaps, even the former dictator himself. Salman cites reports that Burhan has sided with his old boss (who mysteriously disappeared from a Sudanese prison and may or may not be under the control of the Sudanese Army) whose sympathizers “actually fired the first shots on April 15th, against the RSF.”

All of this is wrapped in a web of international intrigue. Saudi Arabia and the United States are leading negotiations aiming at a sustainable ceasefire, although at least seven have come and gone during the past month of fighting. The Russians seem to be on both sides: Salman says that “the Wagner Group is supporting Hemedti and supplying him with arms and military training” and “Putin is directly dealing with al-Burhan” over a base on the Red Sea. Salman also insists that weapons are coming to the two armies from Russia as well as Libya, Chad and elsewhere—and worries that protracted war could spread through the region.

Of course, war is not good for people or for business. The death toll from the fighting is reported at around 600 with many more wounded. Hospitals, water systems and other critical infrastructure have been devastated. Millions have been internally displaced, and thousands are fleeing to Egypt, Chad, and South Sudan. Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, Chad and South Sudan risk losing important imports—everything from gold and oil to grains and livestock—because of the war, which in turn could have dangerous consequences for populations already under pressure.

Is there any ray of hope? Samah Salman insists there must be. “The sacrifices that have been made, the thousands who have been killed in and after the protests and are now being killed in the war currently raging through Sudan…are [not] small marks in Sudan’s history. I think what is happening is on a trajectory where all of this energy is moving towards an inevitable outcome, which is the fact that the up-and-coming generations will no longer accept dictatorial rule in Sudan… And so, I see a point in time where we emerge from this war stronger.”

And then? “How are we going to use that as an opportunity to rebuild Sudan and create a new Sudan for ourselves?”

***

Should the West intervene in Sudan for humanitarian reasons? Let us know what you think in the comment section below

ABOUT OUR GUEST

Samah Salman is an executive leader in Sudan’s private sector with corporate experience in its largest conglomerates with businesses in renewable energy, agriculture, food processing, food security, livestock, oil and gas and telecom industries, with combined $2B in revenues. She also has experience in infrastructure projects (ports, roads, railway) in the East African corridor. She has lived and worked in the US, Italy, London, Dubai and Sudan.

Samah Salman is an executive leader in Sudan’s private sector with corporate experience in its largest conglomerates with businesses in renewable energy, agriculture, food processing, food security, livestock, oil and gas and telecom industries, with combined $2B in revenues. She also has experience in infrastructure projects (ports, roads, railway) in the East African corridor. She has lived and worked in the US, Italy, London, Dubai and Sudan.

Samah has led the planning, development, funding proposals and implementation of large projects in Africa’s private sector. This has included strategic partnerships with government ministries, various DFIs and funds such as the African Development Bank, IFC (World Bank), Green Climate Fund as well as multiple UN agencies. She has also consulted for private equity firms across the Middle East and Africa to help strengthen their portfolio companies. She sits on various advisory boards.

Samah has led social innovation initiatives to address humanitarian challenges in the areas of food security, climate change and renewable energy in Sudan, which is one of the most fragility, violence and conflict-affected countries on the globe. She drove the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ innovations program to ensure that hyper inflation in Sudan would not drive more families to hunger. She was responsible for her company’s corporate venture capital and philanthropy arm that helped to provide early-stage financing to social innovation start-ups in the areas of healthcare, mental health, medtech, agtech and arts and culture. She is currently leading an emergency working group to find innovative ways of addressing the humanitarian crisis created by the newly emergent war in Sudan.

Samah is a graduate of the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, with a degree in Finance and Management. She has won multiple awards and is also a Tutu African Leadership Fellow with the AFLI and University of Oxford. Samah is also the founding President of a civil society organization, USESA, established to support the democratic transition of Sudan.

0 Comments