“In all of the West, we run into a divided society. Those who are smart enough to play on the stock market are fine; they can live. Those who are educated to play in the digital economy are also fine. And those who were the hard-working laborers for distribution and simple workers, they will get lost in the system.” — Kurt Lauk

“Government has not provided the outcomes that are necessary for sustaining democracy.” — Terrence Checki

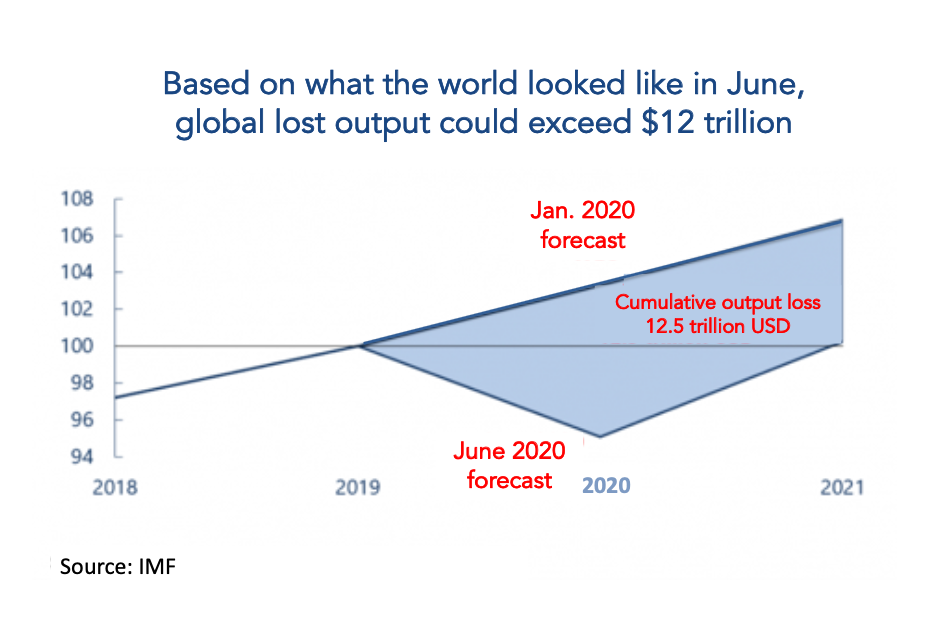

1870. That is the last time the world endured a recession as deep and as global as today’s, according to the International Monetary Fund. And governments have responded with massive spending (at least $11 trillion committed so far), massive money creation (the world’s largest central banks have increased their balance sheets by $6 trillion during the past several months) and almost unprecedented interventions in daily economic life.

The global economy is being reshaped. But will it be better or worse? Seeking answers, Tällberg Foundation chairman Alan Stoga spoke recently with long-experienced U.S. central banker Terry Checki as well as German business leader and former Member of the European Parliament Kurt Lauk for the New Thinking for a New World podcast series.

“The money creation and spending was designed to buy time,” says Checki. “The question is whether or not we have made good use of that time.” So far, he says that at least the U.S. government remains far too devoted to short-term remedies. “We have been using cyclical medicine to treat structural illness,” Checki argues, “and we have administered larger and larger doses to produce smaller and smaller effects.”

Lauk has seen a similar dynamic develop in Europe, where for years the European Union’s “Stability and Growth Pact” gave lip service to fiscal stability. Some countries, Lauk says, have actually pursued sound policy, like Greece (which did “a phenomenal job”), Ireland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany. But states across the south of Europe, especially France, Italy, and Spain, have failed to implement smart economic policies.

“Those countries who have not done structural reforms are now particularly heavily hit by the crisis, and they need more money,” Lauk says. He points to the lack of preparation when it comes to healthcare and infrastructure, and is frustrated that the same countries who failed in the past have come back asking for more: “Now they want the money, unconditional, and the E.U. Commission has basically given in.”

Lauk and Checki foresee another problem as well. Governments are dramatically increasing their direct control of economies, through grants, loans, asset purchases, and subsidies. “I don’t think that the state will give up this increased influence,” Lauk says. Checki points out that, “We’ve intervened in so many different sectors and so many different ways that the normal incentive structures are not operating.” How will this end? They both agree, “Badly!”

The root cause of the problems, according to Checki, is the excessive financialization of modern industrial economies. “One of the reasons [the United States] got into the problems in 2008 was the failure to distinguish between the quantity of growth and the quality of growth,” Checki says. “We have an economy where, prior to 2008, something like 40% of the revenues in the economy were coming from the financial sector. We’ve managed to [let] finance, which is designed to support the real economy, become a substitute for the real economy.”

That contributes to—indeed, causes—economic inequality. “We’ve hollowed out the middle of the social structure,” he says. “We’ve now got an economy that has tech and finance at the very top, and retail and healthcare at the very bottom, and the vast middle, which used to be the backbone of the United States, has pretty much disappeared.”

Of course, the pandemic has made this worse, in both America and Europe. As Lauk points out, “the backbone of the German and European economy, the medium-sized and small enterprises, are basically shut down, and some of them will recover and some of them will not.” This worries him. “I don’t know where the money will come from for those people,” he says, in part because potential growth has declined.

What about inflation? Checki points out that energy and labor costs are rising and that the process of restructuring supply chains—which was already underway before Covid because of the global trade wars—will add significantly to companies’ costs. With massive amounts of new money creation, the result could be a return to the inflation of the past. But Lauk is skeptical because “the purchasing power of the people will go down, and that … could lead to deflation.”

Both of these seasoned experts admit that we are in uncharted waters, which makes forecasts almost useless. As Checki puts it, “We have never seen a situation where the principal risks have emanated from policy, politics, and a massive health challenge” in a context “where the economy was already being challenged by a build-up of pressures that have occurred over the past two or three decades.”

Despite the bad economic news, financial markets are booming—which may seem like a contradiction. “Not at all,” declares Checki. “We decoupled finance from the real economy a long time ago,” he says. “You have markets that are no longer focused on economic fundamentals. They are focused on the activities of central bankers.” The result—markets that defy economic gravity and economic logic—will continue “as long as the central bankers are in the mode they’re in and providing the kind of stimulus and support” to which they have committed.

Taken together, all of this is likely to widen inequality and provoke deep social tensions. “We are probably running into a society which on the one hand is very well-to-do for people with good education, and those who have not a good education—the labor which are needed to run a factory, to sweep it out, for example—they will be lost in the new world,” Lauk says. “This is undermining democracy. We have seen that in many cases in Europe. Those people who are basically outplaced or are thinking they will be outplaced in the new world, vote right or left, which makes democracies less stable.”

Lauk thinks solutions could be found through greater schooling and training—lifelong education. He also believes Europe must find a better balance with digital privacy so that data can flow freely enough for businesses to pursue new opportunities, allowing nations to “innovate out of this mess.” He is confident that a whole range of high-tech industries will boom in the coming years, but remains fearful that they will employ fewer and fewer people. And in aging societies like Western Europe and America, he says, “We have to find a way to compensate people who take care of other people who cannot take care of themselves anymore.”

The problem, Lauk and Checki agree, is that governments have lost their way. “We need to get back to government providing the outcomes and the basics,” Checki argues. “We need policies that will support the population and enable them to recognize their potential.”

And how does the story end if that doesn’t happen? Again, Lauk and Checki agree: “Badly!”

Terrence Checki and Kurt Lauk recently spoke with Alan Stoga as part of the Tällberg Foundation’s New Thinking for a New World podcast series. Hear their conversation on our website or find us on a podcast platform of your choice, (Itunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher, Libsyn, etc).Download the article in PDF here

0 Comments