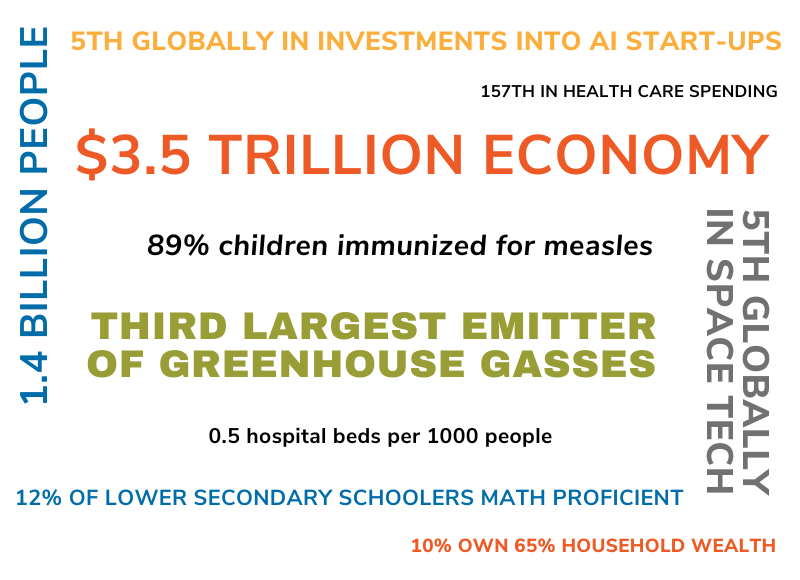

India has always been difficult for non-Indians to understand, maybe for many Indians as well. Sheer size and diversity make governance, never mind coherence, an innate challenge: the world’s most populous nation at 1.4 billion people; India’s most popular state is home to 230 million people; the 5th largest economy in the world, but per capita income is around $2,400; the country’s three richest states are three times richer than the three poorest.

“India is a confederation of extremes,” argues Milan Vaishnav, an expert in Indian political economy (and much else) in a recent New Thinking for New World podcast. He points out that as an independent nation state, the country is only 75 years old and argues the glass-half-full case that what has been achieved is remarkable.

He urges us to think about how India’s dominant leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, describes his country’s dynamic. “Mr. Modi himself would argue that he is seeking not to create something new, but rather to revitalize something old. India was a world power at one point, and as he describes it, had to suffer through 12 centuries of slavery at the hands of all kinds of foreign invaders, not least, the British Raj. And so, what he is trying to harken back to is this idea of India as a civilizational state that has a global presence.”

1200 years is a long leap “back to the future,” even for Europeans used to historical perspectives, never mind for Americans. Does India have any real claim to leadership in the 21st century?

From Vaishnav’s perspective, post-Independence India has developed three powerful tools to harness its complexity.

- “One is democracy. There is a pretty deep-seated commitment to finding peaceful ways of resolving disputes. India isn’t only the poorest country ever to adopt universal suffrage, it’s also the longest standing democracy in the developing world.”

- “The second is that there’s a very elaborate system of transfers…from the central government to the states. The states do the vast majority of the spending, but the center is the one that collects the vast majority of the taxes.”

- “The third part of the answer is that, under the constitution, states have a lot of agency; this is a robustly federal country… On most aspects of day-to-day governance people look to their state capitals and to their chief ministers…not necessarily to the prime minister or to the elected parliament.”

These mechanisms have been critical to India’s hopes to accelerate the pace of development and modernization. Vaishnav says that, in terms of economics, “India has seriously upgraded its investments in the hardware of the economy,” by which he means highways, electricity, water systems, etc. But he also points to the digital payment revolution—1.3 billion Indians have a unique biometric identification number—new laws that streamline indirect taxes, and a new law that creates the possibility of corporate bankruptcy.” He quickly adds that what he calls “economic software” lags: the rule of law, policy certainty, regulatory autonomy. “People don’t want to invest and then find mid-stream that the rules have changed. We see a lot of that in India, whether it’s on taxation, on e-commerce, on foreign direct investment…the list goes on and on.”

Politics are never far from the surface when it comes to India, and a key part of Vaishnav’s explanation of India’s potential lies in Prime Minister Modi and a “much more muscular nationalistic government that is a Hindu-first government.” That’s a two-edged sword: although 80% of Indians are Hindu, that leaves hundreds of millions who are not, including almost 200 million Muslims, “the world’s largest minority.” His concern—“If you upset the delicate balance of democracy and diversity that could, over the long run, have negative economic impacts”—seems a diplomatic understatement in light of the country’s violent history.

Are Modi and his BJP political movement up to the task of balancing democracy and diversity while returning India to a leading position on the global scene? The Prime Minister, who has been in power since 2014 and faces another re-election campaign next year, is clearly the driving force to make the country “not just an economic powerhouse, but…a global geopolitical powerhouse.” According to Vaishnav, for generations, India’s leaders aspired for the country to be a “balancing power.” Modi wants more; “He says, “No. Under my rule, India should become a leading power.”

Modi is incredibly popular in India; polls have suggested that he is the most popular politician in the world. Whether or not that is true, Modi is highly successful in the only way democratic politicians keep score: he wins elections. He was the first Indian political leader since Indira Gandhi to win a majority in Parliament; he repeated that feat in 2019 with a larger majority; early polls for next year’s election suggest he is likely to win big again.

But with great power comes great responsibility (attributed to Churchill long before Marvel Comics’ Spiderman). “There is a big question mark about the sustainability of some of these gains because if Modi were to exit from the scene, would there be a leader, say, in the BJP or elsewhere, who would be able to take this on? There’s no question that he has brought a new energy and a new kind of authority, but also a new concentration of power.” Vaishnav—and many others—worry about the trade-offs: “He’s able to get stuff done, but also is able to circumvent or short-circuit a lot of democratic safeguards as well.”

What’s Vaishnav’s bottom line: is India’s glass half full or half empty? “India is experiencing a geopolitical sweet spot. It is the fastest growing major economy in the world, it has recently surpassed China as the world’s most populous country…it is still feted and courted by all major powers, including Western powers, and we are seeing global companies like Apple and Foxconn looking to India as they offshore from China…This confluence of events has led many people to think this is India’s moment.”

Now his half empty glass. “But, you scratch the surface and there are many questions. Take the economy: India still produces far too few jobs to employ the million people who are joining the labor force every month and will continue to do so for the next several decades…Politically, it has a guarantee of stability in the short-term, but these kinds of social divisions that the current government is stoking, particularly between Hindus and Muslims, could have all kinds of nasty unintended consequences.”

Or, as Vaishav put it in a recent Foreign Affairs commentary, “India may be touted as the next big thing, but as with any marketing campaign, one would be well-advised to read the fine print.”

***

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK: Will India continue its evolution to becoming a global power? Let us know in the comment section below.

Listen to the episode here or find the New Thinking for a New World podcast on a platform of your choice (Apple podcast, Spotify, Stitcher, Google podcast, Youtube, etc).

ABOUT OUR GUEST

Milan Vaishnav is a senior fellow and director of the South Asia Program and the host of the Grand Tamasha podcast at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His primary research focus is the political economy of India, and he examines issues such as corruption and governance, state capacity, distributive politics, and electoral behavior. He also leads a Carnegie research initiative on the Indian diaspora

Milan Vaishnav is a senior fellow and director of the South Asia Program and the host of the Grand Tamasha podcast at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His primary research focus is the political economy of India, and he examines issues such as corruption and governance, state capacity, distributive politics, and electoral behavior. He also leads a Carnegie research initiative on the Indian diaspora

The biggest challenge for India to move forward is to manage the two dominant extremisms which will drag the modernisation and transformation of this country. That is the Hindu extremist and the Muslim extremist constantly at each other’s throat in every walk of life