Is democracy in trouble? The evidence so far this year is troubling: January 6th in Washington, coup in Myanmar, widening arrests in Hong Kong, presidential interference with the judicial systems in El Salvador and Mexico, Polish and Hungarian EU lobbying against “gender equality”—the list is long and global. Some of the sins are big, some small but all of them are consistent with the recent finding by the Economist Intelligence Unit that 70% of countries have exhibited signs of democratic decline over the past year. And that of course doesn’t count the countries that don’t even pretend to be democracies.

The Tällberg Foundation recently hosted a webinar featuring four leaders who are struggling with that decline. Two of them—Peter Biar Ajak of South Sudan and David Smolansky of Venezuela—are in forced exile; two of them—Zuzanna Rudzińska-Bluszcz of Poland and András Léderer of Hungary—are fighting to preserve the rights of groups whom their governments would prefer to treat as second-class citizens (at best).

Despite very different circumstances—South Sudan has never had elections, Venezuela saw an elected leader subvert democracy, and the leaders of the two Eastern European countries prefer self-styled “illiberal” democracy to the real thing—these four have a lot in common. Most importantly, they are struggling to understand the essence of democracy, and then to devise strategies and tactics to make democracy work for their fellow citizens.

Ajak believes that, “You need a vision of society that is widely shared. Otherwise they’re always going to be elements within the society that will pull people to the extremes. And even in societies where such a social contract has already been established, it needs to be constantly renewed because the reality is that the situation is changing. People are changing, priorities are changing. And as a result, what brings the society together is this grand vision.”

On the other hand, Léderer worries that if a vision is too different from attainable reality, it risks producing disillusioned citizens who withdraw from politics, leaving government to activists who might be more interested in personal power. Moreover, he worries that too often democratic advocates “simply focus on institutions…[thinking] that democracy is about having elections every now and then and having certain independent institutions.” But, he argues, that ‘tick the box’ approach produces only the façade of democracy: “How do you make sure that citizens feel democracy is their own, that the institutions are their own, that they have to defend those institutions—not just the buildings, but the very principles?”

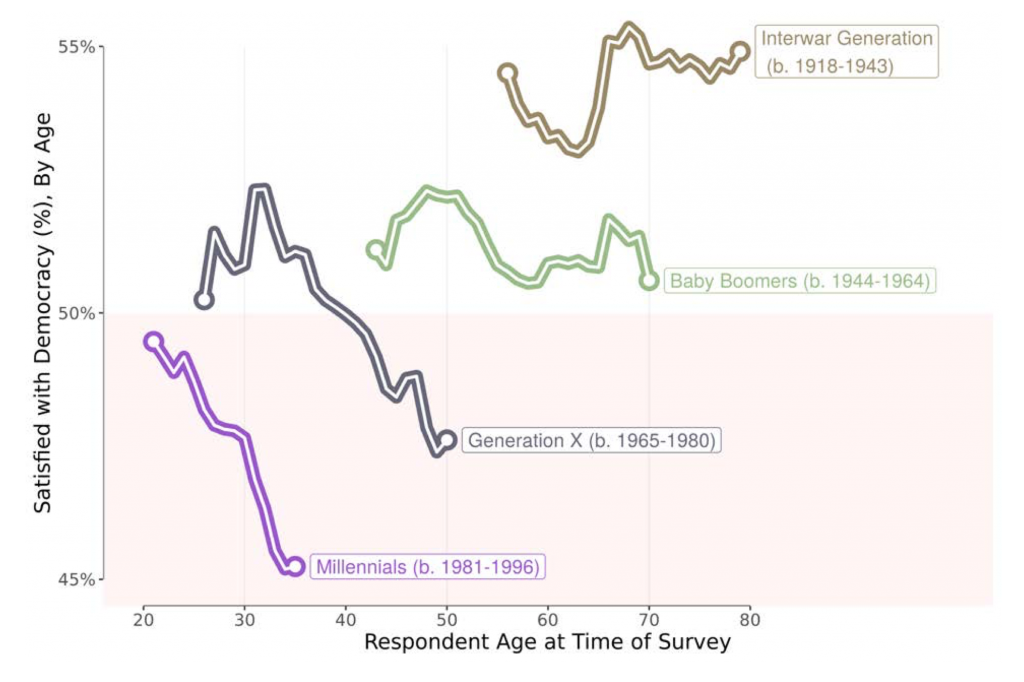

Satisfaction with democracy by age and generational cohort, for 75 countries across the world in all regions. Centre for the Future of Demorcracy, Cambridge UK

In other words, what are the ingredients of the ‘secret sauce’ necessary to produce and sustain a vibrant democracy? Some answers:

- Smolansky: “Transparency and accountability…respect for minorities;”

- Rudzińska-Bluszcz: “Making a civic space…for people to care about small things in their neighborhoods, in their communities that give them a sense of impact;”

- Ajak: “Engaging the people so that democracy…[has] direct relevance in day-to-day life… continuously engaging the population and getting them to care;”

- Léderer: “Always question authority and never accept outright, whatever your most sympathetic leader is telling you…If you don’t have people who participate in public discussions, then the whole story just empties out— you have the empty institutions and the empty shell [of democracy].”

Rudzińska-Bluszcz, who is a human rights lawyer, applies two tests when she evaluates the success or failure of a democracy. “First…how it treats the minorities…I look at how the minorities in Poland are treated—LGBT, women, people with disabilities—those are the main minorities here in Poland. And I look how the government treats them and it doesn’t treat them well. Second…if harm is done, what is the response of authorities and what is the response of the justice system?” On that score as well, she counts Poland as less of a democracy than the one she wants and that she believes Poles deserve.

Of course, democracies require democratic leaders, and Rudzińska-Bluszcz, Léderer, Ajak and Smolansky all believe the men in power in their countries are falling short. Indeed, too often those who attain power try to close the door behind them, sometimes perverting the very forms of democracy and sometimes not even pretending to give democracy a chance. Smolansky points out that in his own case, he won election as mayor—the form of democracy preserved—but then was forced to flee Venezuela to avoid imprisonment. And Ajak reports that the leadership of South Sudan keeps on promising, but postponing elections—there have been no elections since independence in 2011—even though the majority of citizens want to vote.

If democracies need leaders, what are the characteristics of good leadership? Smolansky believes it is the willingness to listen, to be open to criticism and to encourage engagement. “Leaders need to create channels to let people participate,” he insists. Rudzińska-Bluszcz adds that leaders need to be able and willing to take a long-term perspective, beyond election cycles. “The truth is that our politicians don’t look with this long-term perspective. They only look at the polls….and the closest elections. How can you lead a country with such a short perspective?”

Léderer believes leaders need “restraint” which includes knowing when it is time to leave the stage. “Think about leadership as an ever-developing and ever-changing role and position inside the community,” which means that leaders need to know when to say, ‘I’ve done what I wanted to do. Now, let others do it.’ ”

Building on that, Ajak insists that good leaders must “create systems and programs where these [future] leaders are developed and incubated, so that the society will always have a number of different choices from which potential leaders could emerge.”

What path forward? Ajak, seconded by Smolansky, argues for “a limited, but very clear set of rights and principles” that all citizens “commit themselves to carry on for the society to move forward.” In effect, they want to distill the most basic fundamental human rights and the most important principles; this democratic essence would be the constant upon which governments could operate, but never change.

Of course, that approach requires what too few countries have today: trust among people and between those who govern and those who are governed. Rudzińska-Bluszcz has a solution: “Solidarity…I think we should all work together, among the generations, among the differences, despite the walls that have built up. We have to concentrate on common goals like climate change…there are plenty of such issues that we can come up with and work together.”

What if the politicians have different interests, different approaches? Her answer: “Let us do it, the grassroots.”

Power to the people.

Let us know what YOU think and continue the conversation in the comment section below

If you weren’t able to attend the webinar, “Sustainable Democracy?” you can watch the conversation by clicking the play button below

ABOUT OUR GUESTS

Peter Biar Ajak is a scholar, an activist, and a former political prisoner from South Sudan.

Peter Biar Ajak is a scholar, an activist, and a former political prisoner from South Sudan.

He is a Visiting Fellow at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies of the National Defense University. Previously, he was the In-Country Economist for the World Bank and a Senior Advisor to the Minister of National Security in the Office of the President. Peter founded and led several organizations, including South Sudan Wrestling Entertainment, Juba-based Center for Strategic Analyses and Research, and South Sudan Young Leaders Forum.

He is a 2015 Millennium Fellow at the Atlantic Council, 2016 Tutu Fellow at the African Leadership Institute, Fall 2020 Reagan-Fascell Democracy Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy, and a 2021 Young Global Leader at the World Economic Forum. Peter received a BA in Economics from LaSalle University, Master of Public Administration in International Development from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, and a PhD in Politics & International Studies from Cambridge University.

András Léderer is the Senior advocacy officer for the Hungarian Helsinki Committee.

András Léderer is the Senior advocacy officer for the Hungarian Helsinki Committee.

He earned his MSc (in violence, conflict and development) at SOAS, London and his BSc (terrorism, conflict and security) in Aberystwyth and joined the Hungarian Helsinki Committee in September 2015. He writes the Hungarian Helsinki Committee’s regular information updates on asylum for domestic and international audiences and is also working and managing projects of the refugee programme. András is also conducting human rights monitoring visits to reception centers and detention facilities. His PhD research focuses on the relationship of trauma caused by intractable conflicts and speech. He is an Alumni of Leaders Europe: Obama Foundation Fellowship (2021).

Zuzanna Rudzińska-Bluszcz is a human rights lawyer from Poland.

Zuzanna Rudzińska-Bluszcz is a human rights lawyer from Poland.

She was a 2020 candidate to the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights in Poland, supported by over 1200 non-governmental organizations; between 2015-2021 was a head of strategic litigation in the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights of Poland. On behalf of the Commissioner she litigated several groundbreaking cases regarding discrimination, freedom of expression and personal rights’ protection. She has also been engaged in human rights advocacy before the United Nations and Council of Europe. She is an Alumni of Marshall Memorial Fellowship (2019) and Leaders Europe: Obama Foundation Fellowship (2021).

David Smolansky is the special envoy of the Organization of American States to address the Venezuelan Migration and Refugee Crisis.

David Smolansky is the special envoy of the Organization of American States to address the Venezuelan Migration and Refugee Crisis.

He has visited more than 10 countries promoting policies to protect 5.5 million Venezuelans who have fled Maduro’s regime.

He is a former mayor of El Hatillo, Caracas where he led a decrease of 80% of kidnappings and his administration was recognized internationally for its transparency.

Smolansky has been living in exile since 2017 after Maduro’s regime ordered, illegally, his arrest for being one of the leaders who called and participated in non violent protests demanding guarantee of human rights and restoration of democracy.

Interesting read. I’m curious about the graph depicting dissatisfaction among millennials towards democracy. What is the alternative they seek – or is this about their experience of democracy, not the idea of democracy per se?

The data seem to be pretty clear about a generalized turning away from democracy among young people. The reasons seem less clear. They seem to include frustration with outcomes, impatience with the slow pace of democratic processes (especially compared to the immediacy of digital outcomes), and the sense that their participation won’t make a difference (in a world, especially in industrial countries, where youth have outsized influence on cultural and even economic issues). This is less about the abstract question of whether or not democracy is the best form of government or whether they prefer some other form. I think the “strong leader” alternative which comes out from many surveys is a straw man, since there really aren’t any successful examples, at least in western culture.

The risk, of course, is that younger voters either don’t vote—and their frustration rises—or begin to support more radical (left or right), populist politicians. With regard to the former, the consequence is alienation; with regard to the latter, it’s about choices from the fringe because they look like they could change the system. I don’t think young people are looking for simple answers to complex problems, but I do think they are looking for action, as opposed to what they as political stasis.

All of it is very worrying, to say the least.

Alan Stoga, Chairman, Tällberg Foundation