Written by Alan Stoga, Chairman, Tällberg Foundation

“The waters rose and covered the mountains to a depth of more than fifteen cubits. Every living thing that moved on land perished—birds, livestock, wild animals, all the creatures that swarm over the earth, and all mankind…. By the first day of the first month of Noah’s six hundred and first year, the water had dried up from the earth. Noah then removed the covering from the ark and saw that the surface of the ground was dry.”

The Covid-19 pandemic is already far more global than the story of Noah’s flood, which seems to have been based on a deluge somewhere between the Black Sea and the flood plain of the Tigris and Euphrates at least 5,000 years ago. But this pandemic, too, will pass and we are unlikely to need a pigeon to tell us that the virus has run its course.

What will the receding waters reveal?

Will border closings, national hoarding of medical equipment, and finger pointing at “foreigners” for spreading disease transform international relations? Will some countries’ health care systems have collapsed, exposing populations to other, more dangerous risks? Will inter-generational tensions—already high in the West—explode or be calmed by a disease that mostly targets (in terms of fatalities) seniors? Will isolation coupled with newly-found digital habits transform how people relate to each other, producing either more caring, empathetic societies or more “bowling alone” ones? Will we foreswear seeking global solutions to global problems, even if the alternatives of going it alone are obviously ridiculous?

Those, and similar questions, might sound too dramatic, making too much of what after all is a disease that, while it is highly infectious, has low mortality rates and seems to have mild to no impact on most people who are infected. But Coronavirus emerged at a moment in our history when trust in most institutions in most places is unusually low, when politicians are almost universally reviled, when democracy seems to be suffering an existential crisis, and when the dynamic forces of globalization—political, cultural, economic and institutional—are faltering. Context always matters, and the context in which Covid-19 is spreading is one that seems particularly vulnerable to panic.

The spirit of the times, at least in Europe, was captured by President Macron’s stirring declaration this week, “We are at war,” with his Finance Minister adding “This war will be long; it will be violent.” And many Europeans seem to agree as they lock down cities, close borders, restrict travel, and shutter factories as well as “non-essential” shops and commercial places.

War, though, may be in the eye of the beholder. In the increasingly polarized United States, today only 40% of Republicans and 50% of independents think the pandemic is serious, compared to 76% of Democrats—lower numbers for both Republicans and independents than a month ago. Those dramatic differences both reflect and contribute to the withdrawal of the United States from its traditional post-war global leadership role, led by a President who condemns the “foreign” virus, promises a “big” celebration once the virus is defeated and has proposed $1 trillion in cash handouts and subsidies in the meantime.

The old days of presidential calls for shared sacrifice or of constructing coalitions of the willing have disappeared.

But power hates a vacuum: the Chinese, whose initial missteps in managing the outbreak might have contributed to its virulent spread, have clearly decided to try to leverage the crisis to their advantage. As Han Jian of the Chinese Academy of Sciences said, “It is possible to turn the crisis into an opportunity — to increase the trust and the dependence of all countries around the world on ‘Made in China‘.” And Serbian President Alexander Vucic summarized the other side of the equation, “International solidarity does not exist. European solidarity does not exist. The only country that can help us is China.”

The massive disruption of normal life and commerce is triggering a global recession that is in its early stages. Whether it turns out to be greater than the “Great Recession” of 2007-9 will be a function of how long the “hunkering down” shock lasts, the violence with which financial excesses from a decade of cheap money and low credit standards unwind, the size and effectiveness of governmental policy responses, and whether companies simply restart or chose to rebuild global supply chains with an eye for resilience instead of efficiency.

It will also be a function of whether major countries coordinate their policies or, as now seems the case, choose to go it alone. Admittedly, the politicians occasionally tip their hats to old time religion of cooperation, as in the recent G-7 Leaders’ Statement: “We, the Leaders of the Group of Seven, acknowledge that the COVID-19 pandemic is a human tragedy and a global health crisis, which also poses major risks for the world economy.” Unfortunately, “acknowledge” is much easier than actually acting together for the global good.

Back to Noah. What residue will those eventually receding waters leave?

Broadly, I think there are three possibilities.

- One: return to the status quo ante of a system that had been designed for a world that had long since changed and was, at best, barely coping with emerging realities.

- Two: continue on an accelerated path of de-globalization in favor of nationalism and “local” solutions, even in the face of—or, more accurately, in reaction to—challenges like pandemics, climate change and the disruptive consequences of artificial technology whose very nature demand global solutions.

- Three: use the experience of having stared into the Covid-19 abyss to re-engineer systems, institutions, protocols, etc. in ways that might be relevant to the 21st century.

Personally, I doubt the first; fear the second; hope for the third.

Unfortunately, either of the first two scenarios seem more within reach of the current political leadership of the United States, China, Europe, Russia and other major countries than the needed reboot of the global system. Those leaders are failing to coalesce around a shared response to the immediate challenges presented by the Coronavirus crisis; there is literally no chance that they will forego short-term political in an effort to transform how the world works for the common good.

This is especially true for the current leaders of the United States and China who, arguably, would have to find a shared vision before a broader, global solution could be even remotely viable. On the one hand, President Trump is almost completely focused on his re-election and, in any event does the “vision thing” even less well than President George HW Bush who coined the term. On the other, President Xi seems intent on capitalizing on his country’s “first survivor” advantage not only to white wash his own leadership failures, but to double down on positioning China as the lynchpin of an evolved, rather than negotiated, new global order.

Of course, what actually happens during the coming months will matter. Psychologists argue that crisis brings out the best in people, especially in circumstances that do not discriminate—like hurricanes, Blitz bombings, 9/11 terrorism or pandemics. Is it imaginable that voters, at least in democracies, will demand better leaders after they suffer through a tough Covid-19 experience on top of a prevailing sense that their social contracts have failed?

Moreover, massive fiscal spending, monetary easing and regulatory relief—which governments around the world are starting to unveil—could erase much of the post crisis possibility of needed investments in lower carbon infrastructure or of dramatic moves to ease economic inequality. Fiscally exhausted, traumatized governments are likely to be even less ready after Coronavirus than they were before to address the profound challenges that are bearing down on us. What comes after failed governments?

In the end, leadership will matter. We need leaders who are global, committed to universal values, innovative and courageous. Leaders who understand that their role is to take people to where they have not been—but where they need to be.

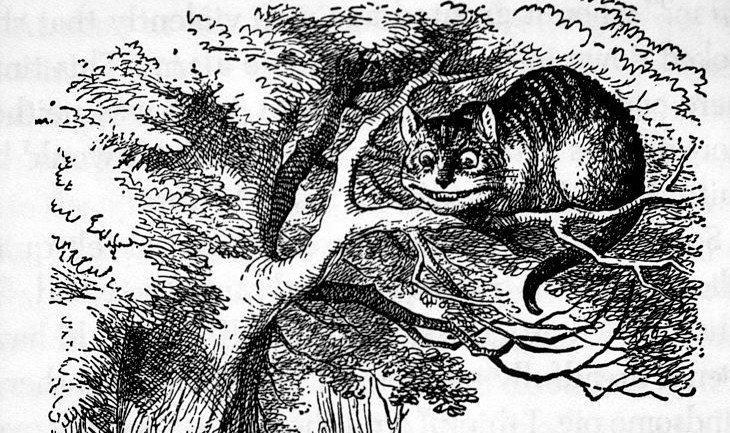

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to walk from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you walk,” said the Cat.

Lewis Carroll

0 Comments