This week the United States inaugurates a new President, much to the joy of many Americans, but to the utter dismay of millions of others. And the swearing in takes place in a Washington, DC locked down, not by fear of pandemic, but by fear of domestic terrorists.

Only two weeks ago, a mob encouraged by President Trump broke into the Capital, halting, for a time, the process to affirm that Joe Biden was elected to succeed Trump and forcing the Vice President, legislators and staff to flee for their lives. The good news is that the mob was expelled, and Biden’s presidency was secured. The bad news is that the events demonstrated—to Americans and to the world—the fragility of democracy in the United States. That fragility is unlikely to be wiped away by Trump’s impeachment or even by a successful Biden presidency.

What happened?

In the November election, a record number of Americans voted—almost two-thirds of registered voters, a rate not seen for more than 100 years. An unusual number of these votes were cast, not on election day itself, but in pre-voting and by mail—in a country where individual state laws define the terms under which citizens actually vote. That unusual electoral rhythm led to all sorts of accusations of fraud, if little proof.

Despite the pandemic, the result was the extraordinary turnout—81 million votes for Biden and 74 million for Trump—which translated into a significant win for Biden in the Electoral College. Both candidates won more votes than any prior presidential candidate.

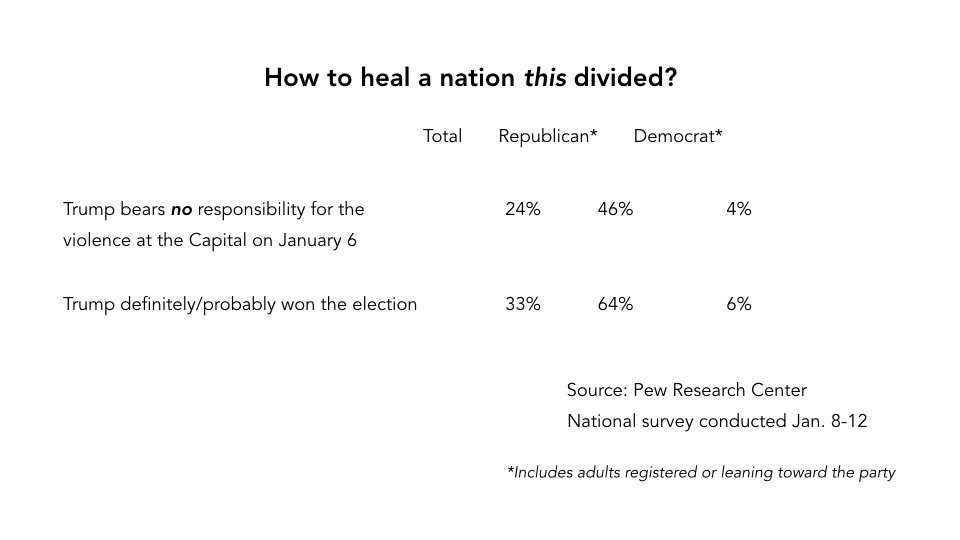

Nonetheless, Donald Trump campaigned relentlessly over the past two months to persuade people that his election defeat was the result of massive fraud—and further, that “all Americans” (code for his hard-core supporters) should demand justice, i.e., recounts that proved his victory whether by addition or by subtraction.  The efficacy of his campaign is measured by the large number of voters who continue to tell pollsters that they believe Trump “definitely or probably” won the election.

The efficacy of his campaign is measured by the large number of voters who continue to tell pollsters that they believe Trump “definitely or probably” won the election.

The irony is that the Republican party had a very good election; up until recent days, there was considerable soul searching among Democrats as to why so many of their candidates lost in the House, Senate and in state legislatures. Indeed, Trump’s 74 million votes is an astonishing total for a candidate widely viewed as controversial, if not radical, by a significant part of the U.S. and global elite.

Since the whole sorry episode was televised, there is little doubt about what happened on January 6. But was is it a “coup,” or “treason,” or “sedition” as some politicians and pundits would have it? Or, was it a bunch of thugs acting out, encouraged by the thug-in-chief and made possible by gross negligence and incompetence (which seems to characterize a lot of government today)? If the former, it was surely strange: no hostages, little property damage, no armed resistance when forces arrived to clear the building, no “Alamo-like” defending the ramparts. Indeed, more flash mob than coup.

That is not to excuse the rioters or Trump; they and he should be prosecuted. Rather, it is to ask whether the people who are selling the “treason and sedition” narrative aren’t themselves contributing to the problem by raising the acts of the rioters to a level way beyond what they deserve? There could be something of that as well in the impeachment of a President who will be out of office when his trial is held, and certainly in the calls by some Democratic members of Congress to remove from office any of their Republican counterparts who supported Trump during the process of ratifying Biden’s Electoral College victory.

Does all this risk setting up a dynamic of dismissing not just the costumed rabble, but all those who oppose the policy preferences of the incoming Administration? Can policy makers and politicians really just ignore 74 million voters without consequence? Is Trump what defines those voters, or something else?

There has been a lot written since January 6 about the failure of American democracy. Really? Is there a credible counter-case that the whole post-election rejection of Trump’s spurious narrative by the courts as well as by the (admittedly antiquated) Electoral College process and the Congress worked admirably, despite the pressure of the mob? It wasn’t pretty and it wasn’t quiet, but it worked.

Perhaps we should be celebrating the strength of U.S. institutions, and wondering how to make them better? How to sustain the enthusiasm of 150 million voters, but transform the anger and fear that motivated many of them into mutual respect and a shared vision?

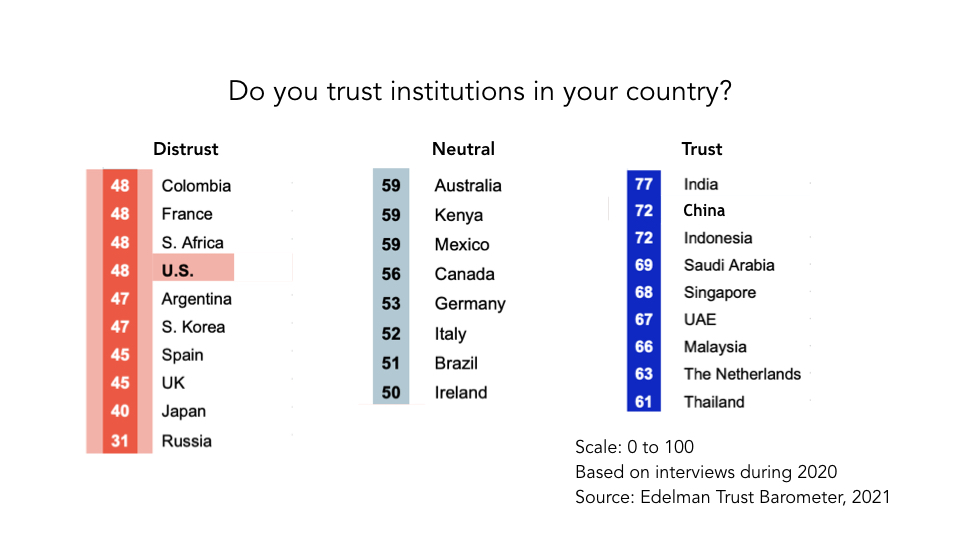

No one takes issue with the idea that American democratic processes designed in the 18th century urgently need to be updated and modernized for the 21st century. What role can technology play? How to regulate the power of social media in forming opinions and reinforcing partisanship? How to narrow the trust gap between people and politicians, between people and institutions? How to make government more responsive? Does U.S. governance need a thorough overhaul and, if so, is the nation capable of a second constitutional convention?

What do we make of Trump? Was he cause or symptom—or simply a one-off accident? How did he capture the hearts and minds of so many Americans? Is it simply that they are wrong, a version of Hillary Clinton’s “deplorables?” If they resist conversion to the Democrat’s “truths,” should they simply be ignored, as some argue? If Trump is a symptom, what is the disease and how do we cure it? If Trump was an accident, will he (and Trumpism) simply fade away like a bad memory once his impeachment trial is over? And, if the Articles of Impeachment are ratified by the Senate, should the Senate ban Trump from future candidacy? Would such a penalty calm or incite more political passion?

What happens in the United States inevitably affects countries around the world, because of its size and power, as well as the structure of the global system. But the United States is not the only democracy struggling with deep political partisanship, lack of trust in institutions, significant segments of the body politic who feel unrepresented by elites, rising inequality, and deep fear of the forces shaping social realities in the early 21st century. And the pandemic has functioned as a kind of pressure cooker that has accelerated and intensified the stresses and strains that challenge our democratic futures.

At the end of the day, the question is whether our democracies—as they now function—are able to sustain the basic social contract between citizens and their governments. Even if we are not sure of the answer, then it is time for profound change.

Alan Stoga

Chairman

Tällberg Foundation

-Thanks for this article, Mr Stoga ! Very serious and important questions, that need creativeness to be solved…