“Basically, we are telling our kids and our grandkids that we don’t care about them when we burn the Amazon… This is something that can’t happen anymore.”

— André Guimarães

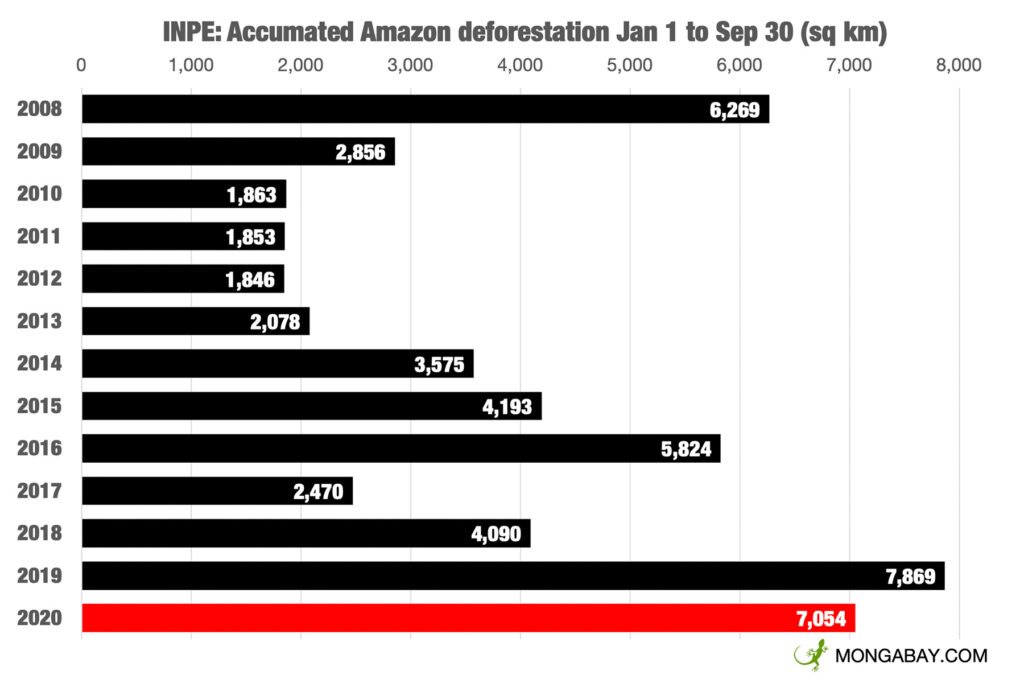

Fires in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest surged in October with the number of blazes up 25% in the first 10 months of 2020 compared to a year ago, according to data from the Brazilian government’s space research agency, INPE. That’s a tragedy not only for Brazil, but also for all of humanity, insists André Guimarães, a scientist and executive director of IPAM Amazonia, one of the premier research organizations studying the Amazon and trying to protect its future.

“I think every single human inhabitant of this planet should be scared to death of us reaching the tipping point,” at which destruction of the rainforest spirals out of control towards dry savannah, or even desertification. Today, about 18-19% of the Amazon has been deforested; scientists believe that that the tipping point could be as low as 20%, and not much more than 25%.

Why does this matter? “About half of the tropical forest in the world is in the Amazon…the trunks, the trees, the leaves, and the roots of the trees in the Amazon, store the equivalent of about 10 years of human global carbon emissions.” That makes the Amazon “crucial for carbon cycles and fundamental for water cycles.”

Guimarães argues that the role of the Amazon global water cycles is particularly important. Forests transport large quantities of water into the atmosphere, no place on earth more so than the Amazon. “One mature tree in the Amazon pumps 500 to 1,000 liters of water to the atmosphere per day. Multiply that by the billions of trees in the biome.”

“Brazil is responsible for feeding somewhere around 1 to 1.2 billion people every day. We can do that because we have free rain out of the Amazon to irrigate our crops,” he says. Reducing the forests reduces the rain—and that reduces food production. “Affecting the rain means that a substantial portion of food production in the world would be affected. Argentina and Brazil together produce around 70% of the soybean [crop] of the world, as well as a substantial portion of the wheat. Corn is also very important. Beef is also crucial.” Global food security would be shattered by a collapse of the Amazon rainforest.

That’s what is at risk today. But Guimarães suspects what we don’t know might be even more valuable. “We are losing biodiversity that we don’t even know of…The Amazon is fundamental to store the biodiversity that will be necessary for our lives in the future: for new medicines, for new food, for new solutions.”

Of course, the destruction of the Amazon rainforest is not new news, but it has accelerated during the first two years of the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro. Guimarães explains that the current government, strongly influenced by the military, is operating with a development model based on the expansion of the frontier: the more land and resources incorporated into the economy, the higher the rate of growth and output. But, “In my opinion, that doesn’t work any more. It’s outdated.” Instead, “We need to replace the paradigm of expansionism with a new paradigm of intensification.”

Guimarães offers an example. “Brazil has about 180 million hectares of pastureland and about 180 million animals on that pastureland, an average of one per hectare. With a little bit of technology—nitrogen for the pastureland, fences, capacity building for the employees, and barns for the animals—you could move from one to three per hectare. So, we can triple the herd of cattle in Brazil without chopping a single tree.”

Essentially, the argument boils down to “redirecting the incentives and the subsidies instead of subsidizing deforestation.”

Put that way, stopping deforestation would seem to be a no-brainer. However, Guimarães points to two huge problems: money and national security or, at least, perceived national security.

“The solution of the deforestation in the Amazon is expensive. You need to monitor, you need to punish, you need to destroy equipment of land grabbers, and other illegal bodies in the Amazon. You have to do that on a permanent basis.” And, of course, the Amazon is huge: about the size of the continental United States, although with only 20 to 25 million people. Brazil and the other Amazon countries simply do not have the capital to solve the problem by themselves.

Moreover, the lack of density—and the fact that a significant portion of those people are members of indigenous tribes who suffer from a kind of second-class citizenship in Brazil, as elsewhere—contribute to the national security issue. The military, Guimarães says, has a vision of the Amazon dating back to the 1960’s and 70’s that makes occupying and developing the region with big dams, highways, and mining projects essential elements of protecting Brazil’s sovereignty. Since military leaders play such prominent roles in the Bolsonaro government, it is not surprising to Guimarães that the current government equates extensive development with maintaining the integrity of the Amazon.

However, he believes this aspect of the problem contains the seeds of its own solution. The military not only has a long-term presence in, and deep knowledge of, the rainforest, but also has many indigenous people in its ranks. “The challenge is to contaminate [their] outdated vision positively with science. So, that at the same time, we can protect the integrity of the Brazilian territory and protect the environmental services like water cycles and the biodiversity, which are fundamental for the current and the future generations.” He firmly believes the military’s deep knowledge of the Amazon territory can be transformed “with new information about the strategic importance of the Amazon. Not just for Brazil, but for the globe.”

That transformation is essential because global actors are increasingly pressing Brazil to reverse deforestation which could excite a counterproductive backlash in the country. “When global investors send letters to the government of Brazil saying that they are concerned with the Amazon, we can see from a half-full or half-empty glass perspective. The half-empty glass is, ‘Oh my God, the world is against Brazil, is criticizing Brazil’… The half-full vision is that ‘the word is interested in what we have here.” Guimarães believes the latter offers a positive, win-win path for Brazil and rest of the world.

At the end of the day, Guimarães is urgently looking for action, based on mutual benefit, cooperation, dialogue, integration, and partnership. “Brazil is probably one of the largest producers and exporters of environmental services to the world. It helps the world in terms of keeping the temperature low. It helps the world have the water cycles that comes from the Amazon and other biomes. It stores the biodiversity which may benefit the future generations. All of that should be observed by the international community, not just from a risk perspective, which is already happening, but also from an opportunity perspective.”

In short, “Protecting the Amazon benefits everybody.”

André Guimarães recently spoke with Alan Stoga as part of the Tällberg Foundation’s “New Thinking for a New World” podcast series. Listen to the episode here or find us on a podcast platform of your choice, (Itunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher, Libsyn etc).

André Guimarães is the Executive Director of IPAM (Amazon Environmental Research Institute). He has a degree in Agronomy from the University of Brasília (UnB) and was Vice-President of Development at Conservation International (CI) Americas, where he supervised the operation in ten Latin American countries. Mr. Guimarães also founded and managed Brasil Florestas, a company that focused on implementing forest products as environmental services. He was the Private Sector Relations Coordinator at the World Bank Pilot program to conserve the Brazilian rain forest and Director of A2R Fundos Ambientais. Mr. Guimarães also managed third sector institutions, such as Instituto BioAtlântica (IBio) and IMAZON.

André Guimarães is the Executive Director of IPAM (Amazon Environmental Research Institute). He has a degree in Agronomy from the University of Brasília (UnB) and was Vice-President of Development at Conservation International (CI) Americas, where he supervised the operation in ten Latin American countries. Mr. Guimarães also founded and managed Brasil Florestas, a company that focused on implementing forest products as environmental services. He was the Private Sector Relations Coordinator at the World Bank Pilot program to conserve the Brazilian rain forest and Director of A2R Fundos Ambientais. Mr. Guimarães also managed third sector institutions, such as Instituto BioAtlântica (IBio) and IMAZON.

0 Comments